I look like I should float, but I sink like a stone. I am told this is due to muscle mass, but I’m not here to brag. I can’t tread water for the life of me, and I can almost walk across the bottom of a swimming pool without holding weights. Thankfully, I am also blessed with a slow heart rate, which allows me to hold my breath for a long time. When I’ve been swimming daily, I can swim the length of an Olympic pool underwater. But I’d never do that in a lake or the ocean, because things live down there.

The thing about swimming pools is that you can see the bottom. In most bodies of water in the United States, that is not the case. (Even before the Supreme Court gutted the Clean Water Act.) I remember swimming in the Delaware Water Gap and seeing the bottom; some blue holes in the Pine Barrens are that clear, to a certain depth. The beaches of the north shore of Hawai’i certainly were, and parts of the Gulf of Mexico. (I’ve noticed that Americans have begun calling it “the Gulf” the same way we call ourselves “Americans” when we share this continent with two other countries. But I guess “United Statesian” never caught on.)

So, it was with much trepidation that I accepted the challenge of

to embark on a kayaking trip on the Potomac River, to see the Ghost Ships. I have never kayaked before. Nor have I canoed.1 And I am certain that you can’t see the bottom of the Potomac anywhere along its snaky length. The only time I’ve attempted to board a kayak was on my honeymoon, on a sea kayak on the beaches of Antigua, and we capsized immediately.Hannah had never kayaked before, either. So we were in the same boat, metaphorically at least, as we did not use a tandem kayak. I think we were glad they were not an option, because then at least we couldn’t capsize each other. I had my new phone on a lanyard, and Hannah had a bunch of expensive camera equipment in a dry bag. If anything fell overboard, it was gone forever. The water was muddy and dark.

Thankfully, our REI instructors taught us well. Neither of us capsized, battered anyone with oars, or crashed into a yacht. Recreational, or sport kayaks are difficult to flip over. The instructors, who both looked like they camped in every season and could start a fire with a granola bar wrapper and clump of wet chai leaves, told us that only people playing with their phones capsized. And I didn’t believe it until we were on the water.

These kayaks are remarkably stable as long as you don’t lean out, which I did not do, because once we were out in the water—which they told us was rarely over six feet deep—we were surrounded by iron spikes and the jagged remains of the Ghost Fleet.

Well over two hundred ships, most burned to the waterline, but all decayed beyond seaworthiness, fill this oddly named body of water. How did they get here?

The history is interesting, if anticlimactic. The wooden ships, which have all rotted to mere iron spikes and rare timbers, were built for the merchant fleet during the Great War. Built of wood due to the scarcity of steel—there’s a sunken concrete-hulled ship off of Cape May, New Jersey, with a similar origin—they were obsolete and unwanted by the end of the war, and most had never served their purpose. The Navy didn’t want to maintain them, so they sold them to a maritime salvage operation which moored them here. Before they could be salvaged, they served a variety of purposes including riparian brothels, and they mysteriously burned when their value was exceeded by the cost of their existence. The American way.

They became an eyesore, then a tourist attraction for kayakers and fishermen, as cleaning up the bay would have an astronomical cost and little gain; the bay sees more use, as people like us come to see the curiosity. It’s an attractive enough area otherwise, but the ships make it unique.

We saw bald eagles, osprey, geese, great blue herons, and cormorants. According to the Merlin bird app, we heard indigo buntings, but I didn’t see any. There was an osprey fishing to feed its fledgling, and we saw it carrying its catch a few times. Here’s the hungry one:

Behind the osprey’s nest is the Accomac, a steel-hulled ship that greets you as you launch. It served a ferry route from Cape Charles to Norfolk until a fire wrecked her, and her owners abandoned her in the bay. Now it’s our problem.

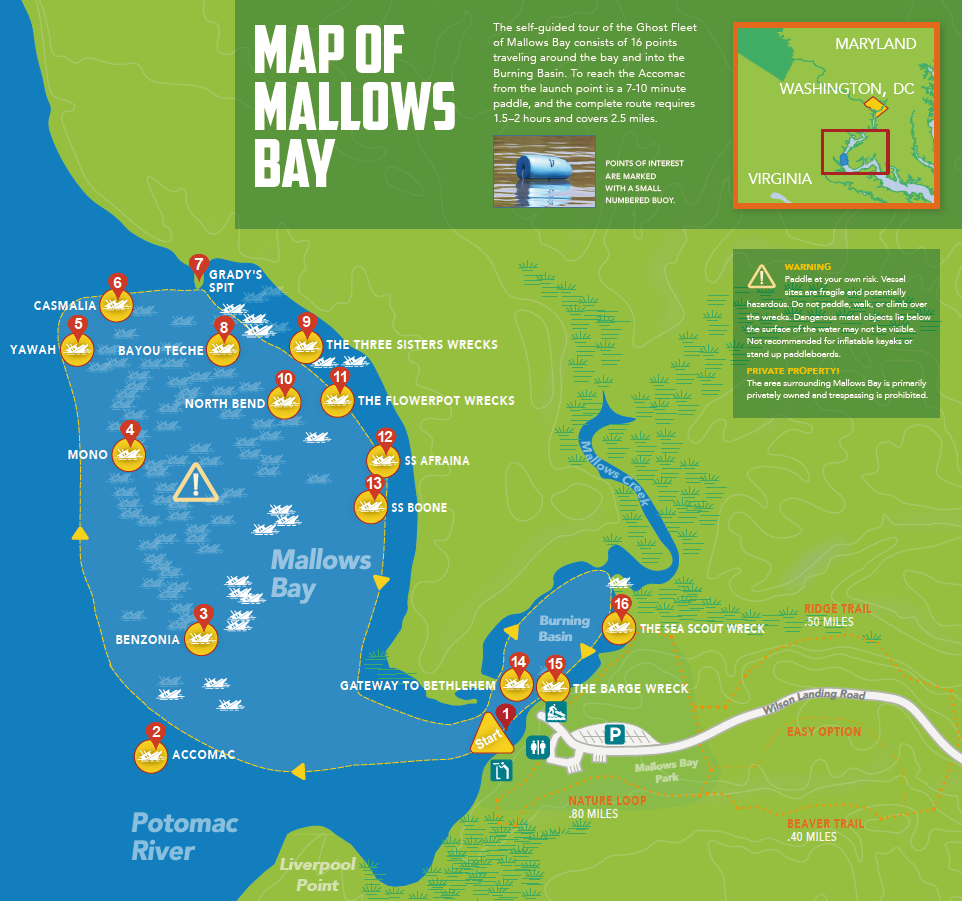

I thoroughly enjoyed this trip, and I am considering purchasing a kayak to explore the Mullica, Batsto, Oswego, and other rivers of the Pine Barrens. This is a map of the Bay; I don’t think we made it to Grady’s Spit. but maybe we did? It didn’t feel like we paddled that far, but maybe that’s because we were having too much fun.

After the trip, we found a local purveyor of delightful fried foods. This time it was Grinder’s Seafood, where I parked next to my car’s twin. A family leaving Sunday crab dinner, had the exact same model and color. The grandmother was so tickled that she asked me to bump fists. Which boded well for our meal. The food was fantastic, from the corn fritters to the fried rockfish po’ boys, clam strips, and crab balls. (I didn’t know they had them).

Here’s a short video of the adventure:

I have however, canoodled with the boy in the boat.

The fried food you guys get to eat! 🤩 I’m so jealous! ((the kayaking looks fun too)

You’re so right about the history -- it was weirdly interesting yet somehow also bureaucratic as hell, like an interesting story that literally took a left turn at DC and became all about defense acquisition spreadsheets. Like if a drama was made up by Bartleby the Scrivener and then some editor added in the brothels at the last minute.

Despite that, it was a wonderful adventure! Thanks so much sharing the terror of kayaking with me -- I had actually been before but it had been years & there is that moment when you think “what the hell am I doing,” but your description of the REI teachers is spot-on, and I felt much better for doing this with a friend so that someone would be able to notify my loved ones when I drowned. That’s so cool about the indigo bunting -- we’ll have to go back again someday to find one, those are gorgeous.