As I was telling a friend who unfortunately is about to learn this themselves, trauma is one of the most enduring memories. The last time I was assaulted was in high school, and I can tell you all about it like it happened only yesterday. That’s the way our brains work; it releases a flood of adrenaline meant to improve our chances of survival by ramping up our ability to focus, but the intensity of the experience burns in on the screen of our memories, and we can often recall portions with unwanted clarity.

For example, I can still see the nostrils of my assailant twitching as he blathered on about “what was my problem,” but thankfully, I don’t recall the impact of the sucker punch that blackened my eye. The next thing I remember, I was strangling him with both hands—one reaching under his armpit and somehow grasping his chin, the other clamped on his throat like a pair of vise pliers. It felt really good, visceral. A reaction to sudden pain. But the hyper-focus distracted me from the three other guys.

I’m not sure how I went from choking him to being face-down on the ground with a knee between my shoulder blades. I later learned that he was on the wrestling team—and my more recent experience in grappling tells me that I had set myself up for an easy takedown. This detailed memory and slow-down still gives me the false impression that there was something more I could have done. I certainly could have behaved differently and avoided the attack, but it was hardly “my fault.” He was looking for trouble, and probably on cocaine; it was apparently rampant in our high school at the time.

The assailant—let’s call him Rob, because that was his name—was one of those dusty blond guys who know they are good looking and not all that smart, but smart enough to know what they can get away with. (He flipped his car and cracked his skull a few years later, and made penance). It began in gym class; I was playing volleyball, and he was playing basketball nearby, and his ball bounced past me. He called for me to get it, and I was spaced out daydreaming, as I usually am, so I didn’t.

Big mistake.

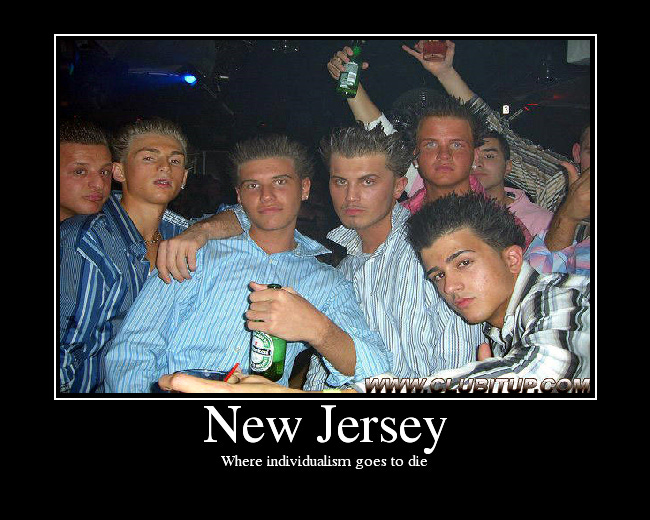

That night, as I waited outside our garden apartment for a ride from my friend—also named Rob, by the way—Basketball Rob and two friends saw me as the drove by and shouted something incoherent. I barely noticed this, because I was once again daydreaming, or “thinking” as we call it. (It’s an affliction we writers endure). Now, Nutley in the ‘80s was afflicted as well, with a subculture of sweatpants-wearing goons of Italian-American extraction, who we called “guidos.” They dated spray-tanned big-hair girls called “guidettes,” and they are what Jersey Shore was all about, except most of those guidos and guidettes were from New York. But I digress.1

Nowadays we call them “jocks” or “bros,” or if you are an aggrieved SF nerd, you call them “dude-bros,” because of the lingering damage from them calling you names. You may not remember this, but being called a “faggot” from a moving vehicle was part of the weather in the ‘80s. It surely was in suburban New Jersey, and from what I’ve read, elsewhere. It’s one reason that we Gen-Xers flinch at the embrace of “queer” by younger LGTBQ, because it’s got more baggage than Louis Vitton.2

So, hearing a bunch of bros scream at me from a moving car because I was wearing a London Fog trenchcoat and engineer’s boots—a full decade before Columbine—was not unexpected. I was a little shocked when they pulled over. I’d never been in a fight, you see. I had been bullied a long time, often due to the daydreaming, but I had never been beaten up; I was kind of big, and also because I mostly ignored it, due to the daydreaming. They pulled over their maroon Monte Carlo and strutted over in their Stiff Stuff-gelled hair and gym clothes, looking very angry.

I remember one of them spit at me. I was flustered from being disrupted from my writing brain; at that time, I was working on short stories that imitated Harlan Ellison, and a novel that melded Clive Barker’s Nightbreed with the sword-wiedling immortals from the movie Highlander, so it’s best that I was disrupted. I might have written that damn thing. Surrounded by three angry jocks, I pulled a cheap switchblade, and also felt myself drop a load in my pants.

I use the passive voice here because there was nothing active about it; I saw three large goons approach me with malicious intent, and the turd appeared in my BVDs like a magician pulling an egg from a stunned audience member’s mouth. Except this egg was not an egg, though it may once have been, and it came out of my ass. I had zero control. My body chose flight, not fight, and decided to lighten the load. I can’t tell you why I didn't run back home; I also can't tell you why decided to share this unsavory detail, except that people don’t talk about it. Like rich people and money, or for that matter writers and money, pants-shitters don’t talk about shitting their pants when they think they’re about to have the shit beat out of them.3

I can tell you this: pulling a knife and shitting your pants, does not frighten angry jocks. (If only I could have wielded a katana like Connor MacLeod, they would surely have broken it in half and beaten me with the scabbard.)To my luck, the other Rob—the friendly, cowardly Rob who drove a 1979 metallic green Lincoln Continental and carried a mini baseball bat for such encounters—rolled up shortly after. I put the silly knife away, and walked to the car.

But Jerk Rob held the door, and dared me to “say something.” Now, for whatever reason, Friend Rob did not pull away. Maybe he was concerned about his door. Jerk Rob, in some sort of cocaine loop, kept asking if I was going to “say something” as we pulled away. And I said, “no.” Friend Rob later commended me on my restraint, but it was of little use; Jerk Rob wouldn’t let go of the door, and Friend Rob wouldn’t drive away, so I stepped out of the car, straight into a sucker punch.

I don’t know why I was suddenly angry about the whole thing; I just wanted it to be over. Instead, I got a bloody nose, a black eye, a bloody trench coat, and embarassment as my mom demanded that we press charges, which led to threats in school and a reminder that our school’s “zero tolerance” violence policy meant that any two participants in a fight on school grounds were suspended. (That was great for bullies who wanted to ruin a smart kid’s grades.) Needless to say, I got the punch in the face. And a few more. I don’t remember how many. Apparently I got him in a headlock before the choke, according to the police report.

The police were as useless then as they are now. The detective said if I pressed charges, the assailants would countercharge. Like our school’s policy, if you fought back, it didn’t matter who started it. The gun nuts have learned that if you’re the only one who can still talk, you usually win. I received similar advice from local males. One suggested that I “get a baseball bat,” and my father’s only response was to ask if I could “take him,” because he could set up a “fair fight.” Pops was still getting into fights in his forties on construction sites, but had neglected to teach me to how throw a punch. (I remember we played “catch” exactly once; I’m a good observer, though, and I did learn how to watch Chuck Norris movies and drink screwdrivers all day.)

I can laugh about all this now, but back then, it was humiliating and violating. I showered off the blood and shit and let the adrenaline take its course. For weeks, I had to deal with the assailants, their friends, and anyone who had heard their story of beating up the weirdo smarty-pants.

The experience sent me to the gym.4 I hit the Nautilus machines and rubbed down with Icy Hot pilfered from the drug store where I worked behind the counter. And like a good Highlander, I would go to the park and work out to “The Power” by Snap blasting on my boombox while I twirled a wooden katana, performed push-ups and squat thrusts until I collapsed in a sweaty mess of B.U.M. Equipment gymwear and Paul Mitchell hair products (also pilfered). With my newfound musculature—and more importantly, my $800 clunker ‘79 Mustang coupe, which kept me from having to wait for rides, or endure the suburban indignity of walking—I was never called a “faggot,” or confronted by guidos ever again.

As Jay Desmarteaux learns in Bad Boy Boogie, the best revenge is living well. One of the crew, whose first name I can’t recall, died of a heroin overdose in the ‘90s. I felt bad for his older brother, who seemed like a decent guy. As mentioned, Jerk Rob cracked up his Monte Carlo, and sort-of apologized to me years later at the drug store, when he was trying to have sex with my boss’s guidette daughter, who made great use of the store’s full selection of Stiff Stuff hair products, which were later purported to contain glue. The jerk who spit at me, has to live with being himself.5

Now, this isn’t much of an assault. But I recall it in this extreme detail to help explain to those who have never endured even this level of trauma, that you can’t choose what to remember. I nearly forgot crapping my pants; I don’t remember much of the fighting. I remember him asking “are you done?” as I was pinned to the lawn, and telling him I was calling the cops. I think writers do victims a disservice when they portray these events in ways that don’t stand up to reality.6 Because you don’t know what you will do, even if you’ve trained for fighting. As Mr Tyson said, everyone has a plan until they get hit.

What brings this up after thirty years? My friend Hannah was attacked by a bunch of teens in a park. She was hurt, but walked home. And I wanted her to know it was not her fault, and that she might stay up at night wondering what she could have done. I told her not to listen to that voice, because I did for many years. I don’t regret all the friends I made at dojos and gyms, but I beat myself up—emotionally, at least—for a long time. Which really, was worse than the bloody nose and poopy pants.

Hannah is a fine writer in her own right, and if you haven’t read what she wrote about her attack yet, I’ve shared it below. If you don’t want to read that, go read her excellent essay on grief in Shenandoah, “The Elephant’s Tiptoe.”

Another affliction of writers. See also, “overuse of footnotes and parentheses.”

See also using “gay” as a pejorative for anything, as in, “that’s so gay,” which white suburban American teens did until recently; also “ghetto,” “lame,” etc. The language of the American teen is its own internalized Saudi morality police.

While I have heard tales of people loosing their bowels when a choke cuts off blood to the brain—most infamously, action has-been Steven Seagal, when Jiu-Jitsu master Gene LeBell choked him after Seagal claimed that he could not be—I think the term “got the shit beat out of me” is simply descriptive of a vicious beating, and any excreta is evacuated by our lizard brain activating the flight portion of the fight-or-flight response as the victim attempts to flee the attack.

It also sent me to the gun shop. You can read about gun culture and male fear in my article, “The Little Gold Colt.”

And having a bully in one of my books named after him.

If I have to read one more fight by someone who’s never been in one, treating it like a surgical strike detailed to the millisecond…

This is so kind of you, Tom.

I was just talking with someone tonight who was urging me to take Krav Maga so that next time I could defend myself. Honestly, in a group of 6-7 teenage males, I’m basically never going to start hitting people -- I didn’t want to hurt her feelings though so I let her tell me all about it.

I guess people want to feel like they’re doing something.

Even as I read this, particularly when I read the parts about your daydreaming, I want to scoop you up and skip you ahead, past the assault. It’s impossible, of course -- so much of what you’ve become clearly got formed around that assault. Isn’t that such a strange thing? That some of the worst things that happen to us can spur our growth?

One of the first things I said to my friend Johnny after the assault was that I had assumed that, given my age & gender, I was unlikely to experience getting punched in the face at this point. And then it turned I was wrong. So now I know exactly what it feels like to get punched in the face.

You’re right that it gets etched deep in there, the reaction, the moments. Still, I like that you got angry Tom, i like that I started shouting, I like most of all that each of us made it through, are making it through.

Thomas (or Tommy, or Tom, or, given the context of this post, TP? What do you prefer, my friend?), this is excellent and honest and vulnerable.

I was verbally bullied as a daydreamy young fat kid, though only by kids much older than me, and never physically because my oldest sister wasn't to be trifled with. Since then, while I've been in the orbit of altercations and have broken up my share, I've never been struck, nor had to strike anyone else. I've taken my share of bloody beatings but those have been on soccer fields and basketball courts.

The thing about fight training is it is also fun! My current regular workouts consist almost entirely of a little running and, particularly, working the heavy bag. It is physically challenging and exhilarating. Just because one gets good at punching doesn't mean you have to punch people.