Before we made cities for the living, we built cities of the dead.

This was supposed to be the first line of a short story, but nothing followed. What came next was thinking about cemeteries, tombs, and necropolises, our stone elegies to the dead, and how building monuments to these painful losses is part of what makes us human.

Grieving is not uniquely human. Many animals mate for life, and do not take a new mate if their one and only leaves them lonely. Funerary rites have been observed in chimpanzees, and elephants mourn like old Italian women. (Italians are not the only culture to employ professional mourners, but I knew one, named Angelina. And she cried at my great-aunt Mary’s funeral like an opera singer.)1

Humans are the only animals known to bury our dead, so unique to us that it made us expand what we define as “human.” Neanderthals buried their dead, but they are kissing cousins, literally. So did homo naledi, a smaller, more arboreal hominin that might not have done as well on Tinder. The empathy we have for those who also experience grief is compassionate, but also selfish, in a way; it makes us less lonely. We are not the only ones to suffer its cold embrace.

But as I said, we are the only ones left who bury our dead; and we are the only ones who built cities for them. The caves used for burials by homo naledi and neandertalis do count, but we went further. Like I mentioned last week, city-states came to be to centralize grain wealth, and the walls were just as useful to lock the citizens in as they were in keeping invaders out. Before we became cogs in the grain machine, we liked to move around, but our dead friends could not follow. So we built homes for them.

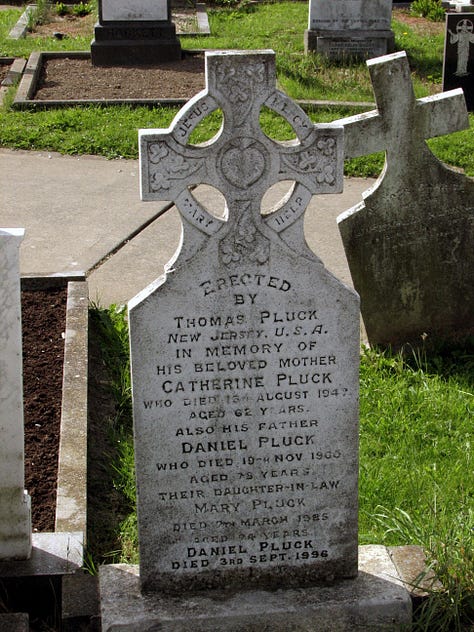

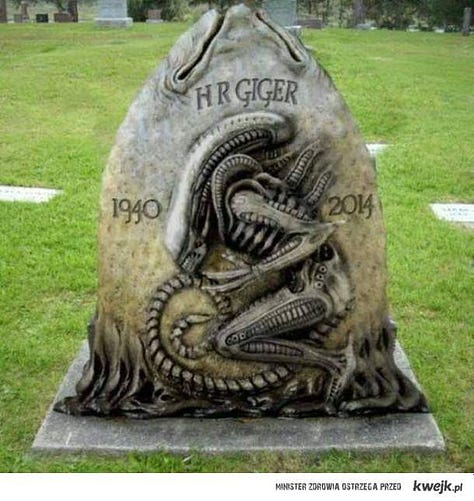

Mounds, at first. Then megaliths to mark them. Stonehenge may have become a giant sundial, but first, it was a necropolis. The bluestones, smaller than the famous sundial sarsens, were there first, as monuments to the dead. It took a long time for us to find what it was for, and I think we enjoyed the mystery more than the catch. Lugging those menhirs all the way from Wales for a sundial? I get it, winter is terrible. I went for a bloody bike ride at sunrise this morning because it’s a warm and beautiful day, the first real warm day of spring. But you could build the sundial out of local stone. But as a monument to your dead? I could see that. I mean, we still do it.

Paleoanthropologists judge a society’s level of inequality by how they bury their dead. Does everyone get six feet of earth, or are people conscripted to built pyramids or earthworks for their eternal rest? In some ancient cities, we buried our dead under the hearth. That seems inconvenient. In other tombs, like the neolithic mounds all over Denmark, the dead were buried and then revisited years later to be honored. I’ve visited the Paris catacombs, where the bones of several million Parisians are laid. At some point, the hearth gets full and you need to rent storage. In New Orleans, they crack open their famous mausoleums and move the bones to the back to make room for more. I’ve never gone on a mausoleum tour in New Orleans, and when I tried to visit the famous cemetery in Savannah, it was closed due to storm damage. I also missed Lady Chablis, may she rest in peace.

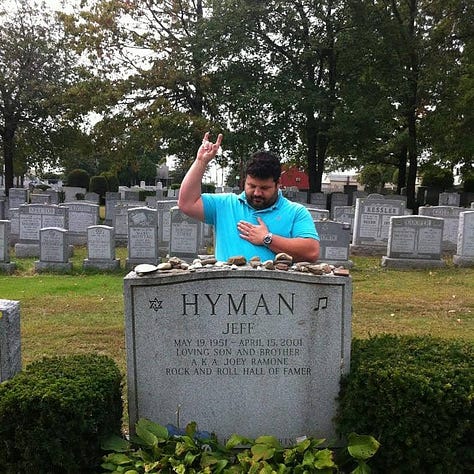

But I do like to visit cemeteries and our cities of the dead. I don’t take stone rubbings, but I have visited a famous grave or two, whether its someone I want to honor, or someone who left an interesting legacy or headstone. I didn’t go to Madeleine Island in Lake Superior just to take a photo of an infamous tombstone that seems to say that the deceased was “shot as a mark of affection,” but while I was there, I most certainly hunted it down. I haven’t visited the tomb of Walt Whitman in Camden yet, but I am told it is megalithic.

Before we got sold on the idea of homesteads, we followed the seasons and the food. Nowadays we sit inside. The cities of the living are less full of bustle, as we huddle in our cemetery caves; they might as well be cities of the dead. Climate-controlled tombs lit by phone screen lanterns.

I am trying to follow my friend, poet Chris LaTray’s lead, and spend 1000 hours outside this year. That’s an hour a day in the winter, and perhaps 5 in July. That’ll be pretty easy, as we have a pool. But in the winter, I am often a homebody. Not this year. We had little snow, and I was out hiking nearly every morning. It improved my mood immensely. This is the first week that my morning walks, hikes, and bikes weren’t in temperatures hovering at the freezing point, and I’m loving it. Rain or shine.

We’ve become afraid of the outdoors. We want a set temperature. I threw the windows open today and let the fresh air in. I’m rolling the windows down in the car when I’m not on the highway. I love the smell of the earth that’s kicked up by plummeting raindrops, I love the hush of walking in the snow. If it had snowed heavily I would have bought snowshoes this year. I didn’t even get to try out my fat tire bike in the snow!

I’ve thought about becoming more nomadic; I love to travel, so does Sarah. But there is something about having a place you call home. Even if it’s a weird ‘70s house in lackluster suburbia, I like having my chair to write this in, with Louie the cat curled up beside me, and shelves of books to choose from. That being said, I am planning a road trip this year to hike and bike around, to make me feel like a hunter-gatherer and also to appreciate having a place to come home to.

Here’s Chris’s post about 1000 hours outside. It’s not as hard as you think, it’s free, and the benefits are great.

I paid tribute to Angelina in my story, “The Cucuzza Curse.”

Thanks for the mention, Tommy! I'm happy you're taking a shot at the outside challenge too. I just came in from a quick 30 minutes out to the main road and back; it's still hovering around freezing here and the weather has been awful. But we do what we must!

As for the interment of the dead, here's a story from my part of the world: one of the many big conflicts the Blackfeet had with white people coming up the Missouri river in steamboats was all the cottonwood trees that were cut to fuel their progress upriver (my great great grandfather Mose La Tray was a woodhawk involved in that labor). The Blackfeet interred their dead in the cottonwoods and the bodies would decompose and fall down into the soil, so the trees were quite literally seen as their ancestors. They didn't like their ancestors being chopped up and burned just so more white people could have an easier trip into the interior to steal everything. Justifiable mayhem ensued.

When you travel across the steppes of Kazakhstan, you see necropolises of yurts, but the yurts are rebar frames with no felt canvas over them, the ghost of yurt, if you will. There are tombstones in these places, too, usually with a stylized ceramic portrait of the deceased on it, which is sad when it is a young person who passed. They are striking places. The only time I had horse meat was when a Kyrgyz colleague of mine attended a ceremony for her uncle, who was an elder, at the 40-day mark after he died. The extended family slaughtered a horse, ate some, and made a white sausage out of the rest, some of which was given to me in honor of the old fellow I had never met. The meat was quite good.