The Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft

And the most terrifying pair of pants imaginable

Some museums, such as the International Phallological Museum, plant themselves in a tourist mecca to lure visitors; others are built in remote villages and rely on their own strangeness to get you to drive several hours to see their secrets. This is one of the latter, in the shrimping town of Hólmavík, three hours drive from Reykjavik on twisty mountain roads along the Westfjord coast. They’ll greet you with a bowl of hot necromancer’s stew and a beer in their cafe, if you make the long trek.

It’s a somewhat bleak little town, with a population of 375 people. The entire region only holds 800, so it counts as the big city in the Westfjords. As I parked outside the museum, surrounded by snowcapped mountains, I realized how remote and lonely the place was, and how much the people would have depended on each other against the elements. You’d think this would foster a strong sense of community, but like mother birds facing a full nest, a ruthless brutality emerged in the mid-1600s as Icelanders turned on their neighbors, accusing them of necromancy and sorcery.

I’ve been to the Salem Witch museum and I was not impressed. They’ve got a big gift shop, but witch hunts in the United States have been glossed over as a rare form of mob violence, not a campaign of terror. Maybe it’s because the victims were mostly young women? In Iceland, the accused “warlocks” and “necromancers” were nearly always men, and the museum dedicated to their memory begins with a memorial to the last such man who was persecuted by his neighbors.

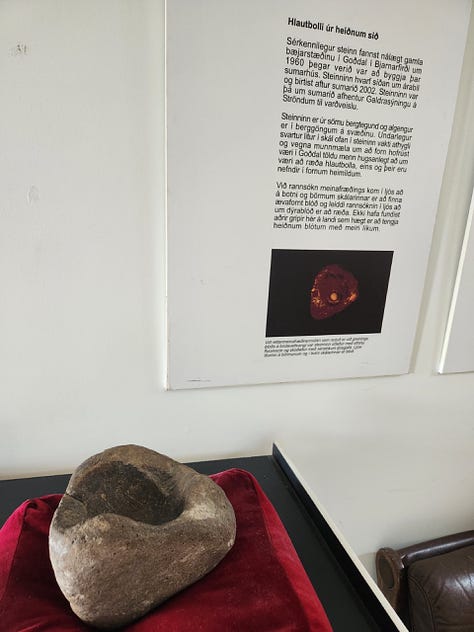

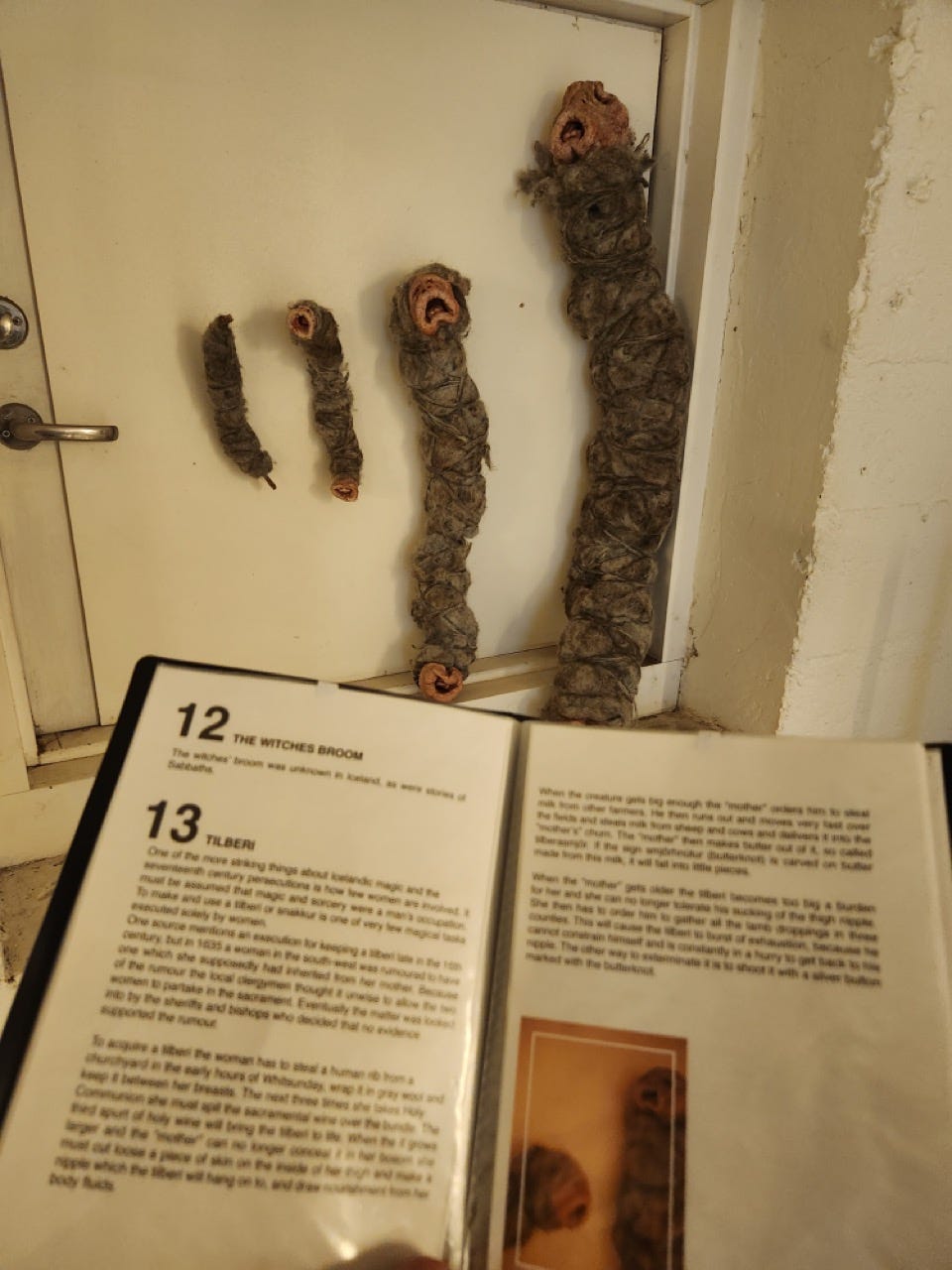

There is a perfect balance of solemnity for the lives lost—most of the accused were burned—and a lighthearted fun with the folklore of magic that was taken deathly serious mere centuries ago. They have many relics of this time, from a sacrificial blood bowl carved of stone, grimoires, and runes, as well as delightfully fun dioramas to visualize the fantastic. My personal favorite is the tilberi, a creature made from a human rib by witches to steal milk from neighbor’s livestock. There’s so much folklore behind it, a two-mouthed furry snake familiar that was fed the witch’s blood from a “thigh nipple” to fuel its misdeeds. If it become too ravenous, it would need to be dispatched by the spellcaster by giving it commands that it must obey but could never fulfill: to gather all the lamb turds in seven counties! Then it would perish from exhaustion.

You can imagine some imaginative crank thinking this up to explain why their sheep wasn’t giving enough milk! It can’t be a bad season, it had to be that old person next door. And they couldn’t simply milk the sheep, they had to make a pact with the Devil and steal a human rib, and use spells to turn it into a vile snake-thing that suckled the nasty mole on the witch’s leg! Then everyone would want to burn that neighbor, who nobody liked anyway. We like to think we’re different now, but we simply use different monikers than “sorcerer” and accuse the persecuted of other things.1

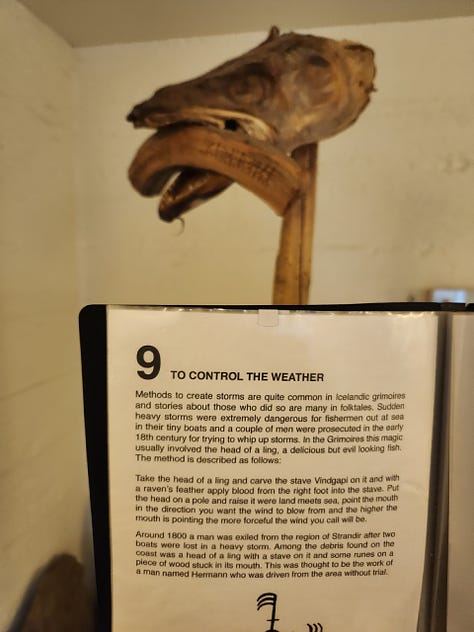

Being a mad-killer sorcerer is hard work! All of the spells seem so complicated. You can enlarge the photos to read the text below and learn how to raise the dead and control the weather. There’s also a blood bowl for sacrifices, which contains remnants of animal blood dating to Viking times.

The pièce de la résistance is the infamous necropants. These were made by skinning the corpse of a man who gave you permission while alive—I suggest asking while he’s drunk—and then wearing them, and finally inserting a coin stolen from a poor widow into the scrotum. Perhaps because of the ballbag’s resemblance to a coin purse, this magic nutsack would then magically replenish itself when the coin was spent, as long as you kept wearing the smelly dead man’s skin. Like I said, necromancy is hard work! It would be easier to work for a living. But where’s the fun in that?

Now, if you don’t want to see the unexpurgated replica necropants in detail, don’t click on the thumbnail below:

If necropants doesn’t put you off your lunch, the cafe is quite good. They serve beer from the local microbrewer, Galdur brewing, and the Sorti black lager is excellent. The “sorcerer’s soup” comes as lamb stew or a bouillabaisse type of seafood stew, and both are delicious!

The museum is not garish or disrespectful, and the memorial to the last man persecuted for sorcery in Iceland, Klemus Bjarnason, is quite touching. There’s a sculpture to him outside.

The text of the memorial reads:

KLEMUS BJARNASON was the last Icelander to be sentenced to death for practicing magic. He was from the Strandir area, born around 1645 but not much is known about him, his family and home, apart from the fact that he was a farmer by Steingrimsford as the lawsuits against him commenced.

Klemus was charged for causing strange illnesses to the two housewives at Hrölberg farm. He had quite a negative reputation from early age and had before been associated with sorcery and magic. The start of the feud with the farmers at Hrolberg seems to be connected to accusations about him stealing a piece of driftwood from a shore nearby.

Klemus denied the accusations but was not allowed to swear an oath pertaining to his innocence because farmers who were called upon refused to swear an oath with him. While in custody at the local constable’s house the next winter, Klemus confessed to knowing a verse for protection against foxes he had recited for his sheep. This verse has been preserved as it was written in the court files.

Similar sorcery is known throughout the Nordic countries from ancient times. These verses recited out loud were believed to protect the sheep from wild animals. The ruling of the court was announced at the parliament at Thingvellir in 1690: “Klemus should be no more permitted to live and burn as a confirmed evil-doer.”

The execution was however delayed and the king of Denmark, of which Iceland was a colony at the time, changed the sentence to a life-long exile from Iceland. Klemus remained in custody though, and a year later was exported to Copenhagen where he died from a fever in 1692.

To this day. around the world. people are still sentenced to corporal punishment or prison, even exiled or executed for the crime of not getting along with their fellow man. This applies especially when an individual’s behavior and appearance is not compliant with local authority. Such persecutions must be fought. Human rights and freedom of expression matter, both then and now.

If you can’t make it to Iceland, or don’t feel like driving three hours from Reykjavik for a museum, you can relive the era of the necromancers in a book. The novel From the Mouth of the Whale by Sjón dramatizes the events of Bjarnason’s life in a respectful and gripping fashion. One of my favorite writers, he brings the tough and mystical world of 1600s Iceland to vivid and poetic life.

Such as voting illegally, welfare fraud, “grooming,” or wanting to cheat at intercollegiate sports.

Ah yes. Both variations here:

https://greensdictofslang.com/entry/3lhwmua#DjAlA60nQdknuT6VXI0AAD3iYByc-nyz

Search on ‘scrotum’? I see 30 and ‘male genitals’ sees 72 in the zone.

bag, n.1

ball-bag (n.) under balls, n.

balls it (v.) under balls, n.

beanbag (n.) under bean, n.1

biffin, n.2

bo-jack, n.

bollockbag (n.) under bollock, n.

bozack, n.

bozak, n.

cockbag under cock, n.3

crankcase, n.

daddy-bag (n.) under daddy, n.

dick sack (n.) under dick, n.1

grand bag (n.) under grand, adj.

happy bag (n.) under happy, adj.

jelly-bag (n.) under jelly, n.1

jewel box (n.) under jewel, n.

lather-box (n.) under lather, n.1

nad-bag (n.) under nads, n.

nutsack (n.) under nuts, n.2

pocket, n.

purse, n.

raisin bag, n.

rantallion, n.

sack o’ nuts (n.) under sack, n.

sack, n.

saddlebags (n.) under saddle, n.

satchel, n.

scrote, n.

whiffles, n.