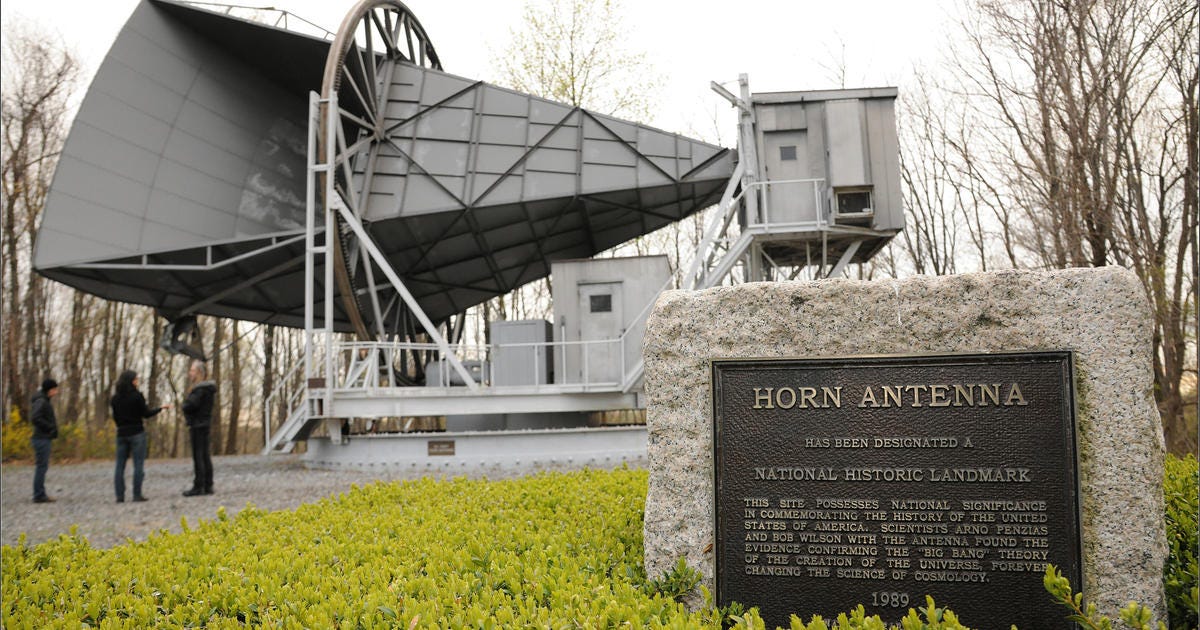

A short distance from where the transistor was developed, on an overgrown mountain surrounded by abandoned buildings, sits an unassuming chunk of metal that was instrumental in humans learning how the universe began.

A few weekends ago, as I drove to join my sister in seeing the hilarious comic Jessica Kirson in New York, I made a detour to visit both Bell Labs, where the transistor was developed—along with the laser, the modern solar cell, the Telstar satellite, and the UNIX operating system—and the Holmdel horn antenna, which collected the fuzzy background noise of the universe, which Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson identified as energy from the Big Bang.

The “Holmdel Horn,” as it is called, is in danger of destruction. Like all things in New Jersey, some developer thinks it would be better demolished to make way for some overpriced housing. The grounds are gated, and if you park your car and walk on foot, the paths are barred. What should be a museum to the discovery of the beginnings of all creation is a slowly decaying campus awaiting demolition so some rich man can get richer. If you’d like to sign a petition to stop its destruction, fewer than ten thousand people have done so. Please join us in this fruitless quest to stop New Jersey’s desire to pave every square inch of its land.

The photo is not mine; I didn’t trespass to see this artifact before it’s gone. Perhaps I should have. I imagine that the compromise will be stuffing the horn in some disused warehouse and allowing visitors every sixth Tuesday with a reservation in advance. Then when nobody is paying attention, it will be sold for scrap. The land it’s on is worth too much; homes in the area sell for millions of dollars. A piece of scientific history may be priceless, but that also means worthless, if a powerful man can’t profit from it.

To prove the point, let me show you the glory of BellWorks, once known as Bell Labs.

It’s rather beautiful, a broad butte of polished glass before a lake where cormorants dive, and the scientific research lab which helped conquer space and put a supercomputer in your pocket is now an office park with shops, a public library, a driving range, and an outdoor roof deck bar. To survive, it had to adapt. You can’t expect that land to sit fallow as a stuffy museum to discovery when it could house several luxury boutiques. As Robert Frost would say, “provide, provide!”

The inside is immense and somewhat awesome in the way the Bradbury Building must be. But like its discoveries, it is cold and rigid, a black and gold maze like the microchips its transistors helped create. The signs for its high end shops are dwarfed by its scale, but they are there, easily located via six-foot-tall touch screen directory systems. I didn’t have time to peruse the library, and Bar Bella, which serves drinks on the outdoor second story roof deck, is only open Wednesdays to Saturdays, and I had the ill fortune to arrive on a Tuesday. I couldn’t drink a beer where UNIX was developed!

The UNIX operating system was first developed to manage telephone switches; it’s Bell, after all. Ma Bell! But now it’s everywhere. If you’re using a Mac to read this, MacOS is based on FreeBSD, which was written in Berkeley after Ken Thompson took Bell’s UNIX there. And of course, Linux is everywhere, a free source version. The version I learned on at Rutgers was IBM’s AIX, based on UNIX System V, released by AT&T after Ma Bell was split up. I majored in English Literature, but thankfully Professor Hodgson, who taught an interdisciplinary course that taught both science and science fiction, demanded that every one of his students create a login at the computer center, which granted me my first email address: pluck@andromeda.rutgers.edu

All the servers were named after galaxies. This was 1988, and the World Wide Web was a baby. Netscape Mosaic was the browser, run from Xwindows or on a PC, after you connected using Trumpet Winsock to get a TCP/IP stack. Later, Microsoft would use BSD UNIX code to implement TCP (transport communication protocol) on its operating system. I learned by doing, playing with the UNIX shell, which eventually paid off when I moved to Minneapolis to look for a job at West Publishing, and a hiring freeze and a transit strike quashed my dreams. I took a job doing call center support for Target’s bridal registry kiosks, which led to a call center job for a Point-of-Sale company, who used UNIX systems. Late one night, covering the phones, a UNIX admin needed help, and my account didn’t have privileges (this was before sudo was public, if any UNIX nerds are reading). While he tried to figure a way to have me fix something without giving me the root password, I kludged a way through it (using chmod and by copying executables to my home directory, I think. It’s been over 25 years.) This impressed him, and he offered me a job on the UNIX team. I took that job in 1997 and never looked back.

Now I’m more of a project manager, but my UNIX skills still come into play every day, whether I’m helping a customer debug a PowerShell script as a favor, or using grep, sed, and awk to fiddle with files using Terminal on my MacBook because search and replace are just so, so tedious. So visiting Bell Labs was a pilgrimage to me, to see the place where the computer operating system that permitted me a handsomely-paying career was developed. To run phone switches. I’m also a bit of a telephony nerd, or was, when it was old and switch based. I handled POTS lines (Plain Old Telephone System) at the docks when I worked there, and until fiber optic cables took over, T1 lines ruled the land—24 phone lines bundled together, to create 1.544 megabytes per second. If you’re old enough to remember 56k modems for Internet connections, this was 24 of those. But that’s all ancient history now.

The roof deck at Bell Labs is impressive even if you can’t get a drink up there. The next time I’m driving near Holmdel on a Wednesday through Saturday, I will make a short detour for a bar bite and a beer, to salute the OS that pays my bills, and cheer rm -rf /tmp/braincell to no one in particular, a joke only I’m likely to get.

I hope the Holmdel Horn is saved, even if it must be commercialized like Bell Labs. The campus it’s on is quite beautiful, on a mountaintop, with easy access to the highway. Instead of luxury townhomes, we should be building a telescope and a planetarium up there, and maybe a couple windmills to power them. The horn helped us “see” as far into the past as one can, to measure the wave patterns of the explosion that created us all. Now, we must look to the future. Will we pave over a lush mountain that’s home to a scientific marvel, or will we preserve its beauty and history?

Only time will tell.

I love a good pilgrimage.

“I took a job doing call center support for Target’s bridal registry kiosks.” Um. TELL US MORE.