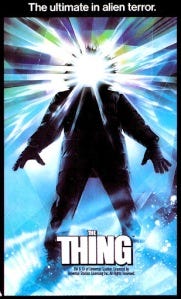

John Carpenter’s The Thing has long been a favorite of both horror and science fiction fans for its perfect mood, taut pacing, and its faithful adaptation of John Campbell;s unforgettable short story, “Who Goes There?” Written in 1938, the SF tale predates the Cold War paranoia of the Body Snatcher films, and touches an existential, primal childhood fear of the unknown. Are people what they seem to be?

Wouldn’t we like to know!

The opening credits, with the dissonant, haunting score thrumming in the background as a helicopter follows a sled dog over the endless, snowy expanse of the Antarctic wasteland, is how most of us remember the story beginning, but first, we see our lonely planet in the darkness of space. But it is not alone; an object circles, then crashes and burns into the atmosphere. A tiny flaming speck, like an insect or even a virus to the massive planet, and we know how dangerous those tiny things can be. Every scene sets a paranoid, chilling mood that eases us into willfully suspending our disbelief for the fantastic tale to come, of an invasion on a cellular level. We then cut to the barren wastes of Antarctica, where a handsome sled dog flees across the snow, and looks back over its shoulder at its pursuers in a way a dog never would. A man with a rifle shoots at it frantically, panicked beyond reason.

The dog heads toward a research station, where we meet our only companions for the rest of the story, with no introduction. They seem pretty laid back except for the one man in uniform, Garry, who represents the only presence of authority in this remote outpost at McMurdo station. He is disrespected by his peers, treated almost as a joke. The others are misfits and fierce independents: bikers, mountain men, cowboys, MIT computer nerds. The doctor wear a nose ring. They have either chosen this place away from the rest of society, or would be accepted nowhere else. We never even find out what they’re doing out there, except escaping the shackles of civilization. What are they studying? It’s never mentioned.

The dog runs into their camp as they come out to investigate the approaching helicopter. Their visitors immediately wound one of them, trying to kill the dog. They shout in a foreign language, and their aberrant behavior—who would want to kill a dog that isn't attacking anyone?—is taken for cabin fever. They die before any explanation can be given.

I don't intend to synopsize the film, or do a shot by shot study of it, for that has been done many times before. There are entire websites devoted to it, such as Outpost 31 or these reviews by people who've actually lived in Antarctica. I'm more interested in what makes the film so effective, and popular enough to spawn a prequel 30 years later. And yes, my expectations are quite low for that film, even if it ends with two Norwegians, the last alive, chasing a dog across the snow in a helicopter. Carpenter’s version has been called a remake of the 1951 Howard Hawks film The Thing from Another World, but that ignored the premise of “Who Goes There?” and went off on its own, and I do not consider this a remake at all. Nor do I find it beyond criticism.

Carpenter went with an all male cast, even though women served in Antarctica since the ‘60s. Maybe at the time, he would have been pushed to include a romantic subplot or a nude scene, and wanted to avoid it? I like to think that Norris and Doc Copper were a secret couple. (Which makes the film’s most infamous defibrillator scene all the more haunting.) Maybe that's what Doc's nose ring signified? That's a nice little touch that we notice again now that big screen TVs and HD transfers are commonplace, that Doc has a nose ring, very uncommon in the '80s, showing him to be a bit of an odd character like his compatriots.

The story isn't perfect; do we ever learn who sabotaged the blood supply? Like that murder in The Big Sleep, where even author Raymond Chandler was hard pressed to explain who did it? Some things are best left unexplained. I don't want to know where the aliens from Alien come from; I didn't want to know about Hannibal Lecter's childhood, much less Michael Myers. The unknown is an important function of horror, and coupled with the isolation of the Antarctic continent, the paranoia of the hidden menace, and the fear of a death that ends with your identity truly stolen, The Thing offers up a panoply of terrors from the beginning. The creature itself, a mockery of the human form, doesn't just steal your face or your corpse; it turns your organs into modern art sculpture and uses them as weapons. Including a flower of dog tongues that H.P. Lovecraft enthusiasts love to point out, because it resembles the Elder Things from his novella “At the Mountains of Madness,” and Carpenter is definitely a fan of his work. Not until a year later with David Cronenberg's Videodrome would body horror stand on its own; here at least you're dead and simply being mimicked by a ruthless organism. Cold comfort. Or is it a virus? A prion? It’s never explained, and that’s as it should be.

Another risk taken is the ambiguous ending, which thankfully never spawned a film sequel. There was a comic book mini-series called The Thing from Another World that begins with MacReady being rescued. I never want to know if Childs or MacReady are real, or a thing. It is unnecessary for the story, and it robs us of that unease in the pit of our stomachs when the unsettling soundtrack rises up for the end credit roll. Mac and Childs are slugging whiskey, watching the camp burn, and the two men—or the man and the thing—will be frozen statues staring each other down when the rescue team come after the long winter.

The script by Bill Lancaster—whose only other credit is another fave of mine—The Bad News Bears—is so sparse that Carpenter's direction seems to fade into the background, as if we’re watching a documentary. The reveals often occur in the back of the frame, like the famous spider-thing head that tries to sneak off on its own. The rest is close, accentuating the cramped quarters of the compound or the loneliness of the outpost, with nothing but mountains for miles and miles around.

My favorite scene is the death of Bennings, or rather thing-Bennings, where the creature falls int the snow, after being chased, before fully assimilated. In a rare moment of weakness for the monster, it howls at his pursuers before they torch it. Or is it the last remnant of the real Bennings screaming in terror before his friends burn him alive to save themselves? Either way, it is unforgettable. Apparently a much more complex death scene was planned but scrapped due to cost, and this haunting one takes it place.

It was a brave thing for Carpenter to tackle this one after getting panned for The Fog; he could've done another slasher, or another post-apocalyptic hit like Escape from New York, but he once again chose to go in a new direction. Something we'd never seen before, and one we are likely to never see again, with the advent of computer generated effects. Pioneers Rob Bottin and Stan Winston used every trick in the book, even stop motion, to create the Thing, and its visceral design is effective even today. I know, as I watched it with my niece—who had watched the good, but inferior prequel on cable by herself and wanted to see the original. She’s a digital native, yet she was captivated by this slow, thoughtful, careful film from the opening scene. She was ticked off by the ending, so we talked about it, and who she thought might be the Thing. And gave the best answer: she didn’t know, but she’d never stop thinking about it.

On occasion you can see the movie’s slip showing; there’s a scene where the movement is reversed and it sticks out a little. But when Doc Copper gets his hands amputated and his patient’s head tears itself off to escape, your sense of disbelief is suspended. It is some of the best of the traditional model work you'll ever see, until the animatronic dinosaurs in Jurassic Park scared the hell out of us. Carpenter took this level of detail down to the title sequence, paying homage to the 1951 Howard Hawks film, which due to budgetary concerns changed the original mimic creature into a plant-based, bloodsucking lifeform that brought its own set of challenges.

I don't think of this film as a remake, but another adaptation of the story, one truer to the simple question it asks: what if something could mimic us perfectly, down to our personalities; would that really be us? Taken over cell by cell, betrayed by our own DNA, would we know we were a “Thing” until it decided to strike our friends, or defend itself? The film never answers these questions, but does ask them. The film was both a commercial and critical failure upon release, panned by viewers and critics alike for its brutal gore and bleak ending. Being 11 years old at the time, I never had a chance to see it in theaters, but it was one of the first movies I taped off HBO, and watched over and over. Along with Alien and Poltergeist, this was one of the formative films of my early years. Skinless, bizarre dog-like creatures populated my nightmares, along with living hungry trees and sleek, sexy, biomechanical monsters. IMDb trivia states that this is Carpenter’s favorite of his own films, and I have to agree.

This post was written for the John Carpenter blogathon this week at RADIATOR HEAVEN. Make sure to go there and check out J.D.'s posts there. I always learn something new, even about films I've seen a dozen times.

I came to The Thing a little later and don't have nearly the same relationship with it you do but I remember loving it. I'm going to revisit it sooner than later.

This comment is not about “The Thing” movie exactly since I’ve never actually seen it (though your description makes a good case for it -- if I could watch scary movies, which I generally can’t)... However, the premise and the original story title of “Who Goes There?” made the following clip pop into my mind. It reminds me of the situation we all face all the time of trying to assess who people are down deep -- and who we are too. We all have our moments that are not our best. Except “The Thing” who apparently is 100% evil 24/7. Different movie below, but maybe some resonance on that particular level?

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=4G7py-x4kMw&pp=ygUVbG90ciBmcm9kbyBhbmQgYmlsYm8g

I do like how in this case, the character can come back to himself and acknowledge what has happened. He’s not fully The Thing. ☺️ The Thing is not a nice guy.