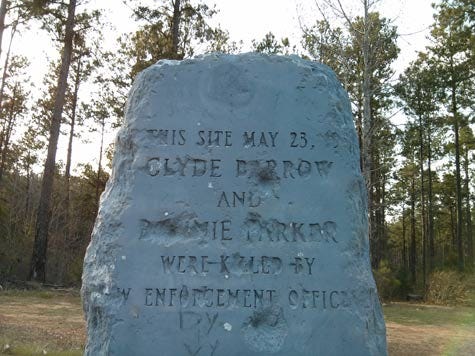

As I rounded the curve of scrub-speckled highway in Bienville Parish, not far from the Arkansas state line, I nearly blew past the concrete marker I came to see. I pulled the rented land barge onto the gravel patch on the roadside, and we stretched our legs before we approached the bullet-pocked monolith.

Wilted flowers have been left at its feet. Stones placed on its head. Chips gouged away as souvenirs.

The concrete marker reads:

THIS SITE MAY 23, 1934 CLYDE BARROW AND BONNIE PARKER WERE KILLED BY LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS

I am at the final battleground of two of the last century’s most notorious criminals, and I came with a distant relative of one of the lawmen who participated in the deadly ambush.

Dapper Dillinger may have been the most famous of the Depression-era bank robbers, but few duos evoke the glorified outlaw romance like Bonnie and Clyde. Like most of their kind, their exploits were exaggerated and distorted by law enforcement, historians, and the press. Robin and Marian they were not. The Barrow gang did not hesitate to murder civilians and lawmen alike. They did not rob to fund a lavish celebrity lifestyle like Dillinger. Some history buffs say Clyde stole to fund a war against the Texas prison system after he was raped and abused inside.

Bonnie Parker is a figure of some contention in ’30s bank robber history. Some argue that she never fired a shot. Others claim she wore a .38 strapped to her leg, and used it. Her gun moll image is based on photos left behind in their hideout in Joplin, Missouri, that show her posing with a pistol and cigar. What is not disputed is her death scream, when a posse of lawmen—including my comanion’ss distant relative, Sheriff Henderson Jordan—emptied several Browning Automatic Rifles into her and Clyde Barrow’s V8 Ford on a remote highway outside Gibsland, a small town near Shreveport.

Clyde Barrow grew up dirt poor, sleeping under his father’s wagon when his family left the farm for Dallas. He stole as a youth, probably to not go hungry. That got him sentenced to labor in Texas on Eastham Prison Farm, where a fellow inmate raped him repeatedly. Barrow beat the man to death, and as expected, came out changed by the experience.

“He changed from a schoolboy to a rattlesnake,” crook-in-arms Ralph Fults said. That’s where the stories of revenge come from, but other than a prison break that left a guard dead, and set the Texas Rangers on their tail, there is no real evidence of an anarchic war against authority. Once you commit to a career of armed robbery and murder, there aren’t many options left.

But their story lends itself to such imaginings. Clyde met Bonnie Parker at a friend’s house, where it was said they were smitten with each other. Bonnie tagged along on his robberies with the gang. She wrote tragic poetry, like “the Story of Suicide Sal” and “The Trail’s End,” which no journalist could resist. After their Ford crashed during an escape, she suffered third-degree burns on her leg that crippled her until the day she died. She had to hop on one leg, or Clyde would carry her. They were caught in part because purchasing the medicine for her unhealed burn made them easy to trace.

As Barrow’s rattlesnake personality struck down more law officers and several civilians, the public no longer saw the couple as outlaw lovers defying authority, but as cold-blooded murderers who needed killing. But they hit the hated banks, so there was that. The Dust Bowl, one of the greatest environmental disasters on record, and the suffering that banks caused by acting like farmers could somehow pay their bills after the center of the country became a desert, is given short shrift in American history. It’s tied in to the Great Depression, like something that just happened. Because some rich men jumped out of windows, it is treated like an Act of God rather than something that occurred due to capitalist practices that enriched those who caused it. So it was hard to hate the robbers, unless they hurt you or yours personally.

I returned to this article because of “Getaway Driver,” written by Lauren Hough, where her grandfather talked about meeting Bonnie and Clyde. It’s worth a read.

Sheriff Henderson Jordan served as infantryman in the Great War. Earlier ambushes on Barrow’s Model B Ford had failed when the Thompson submachine guns did not pierce the auto’s metal frame. Sheriff Jordan and the rest of the posse, led by former Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, armed up with Browning Automatic Rifles firing the powerful .30–06 cartridge and Remington Model 8s, .35 caliber rifles with extended magazines.

When Sheriff Jordan (pronounced Jur-dan) learned that Bonnie and Clyde were passing through to rob a bank in neighboring Natchitoches Parish, he took no chances. He cajoled the father of gang member Henry Methvin to jack up his truck on the road as if broken down. When Barrow slowed to offer assistance, the posse opened fire with their battle rifles, unleashing 130 rounds before switching to shotguns and sidearms. The smoking vehicle veered into a ditch, and the men fired until they were absolutely sure that Barrow, known for gunning his way out of many a tight spot, breathed no more.

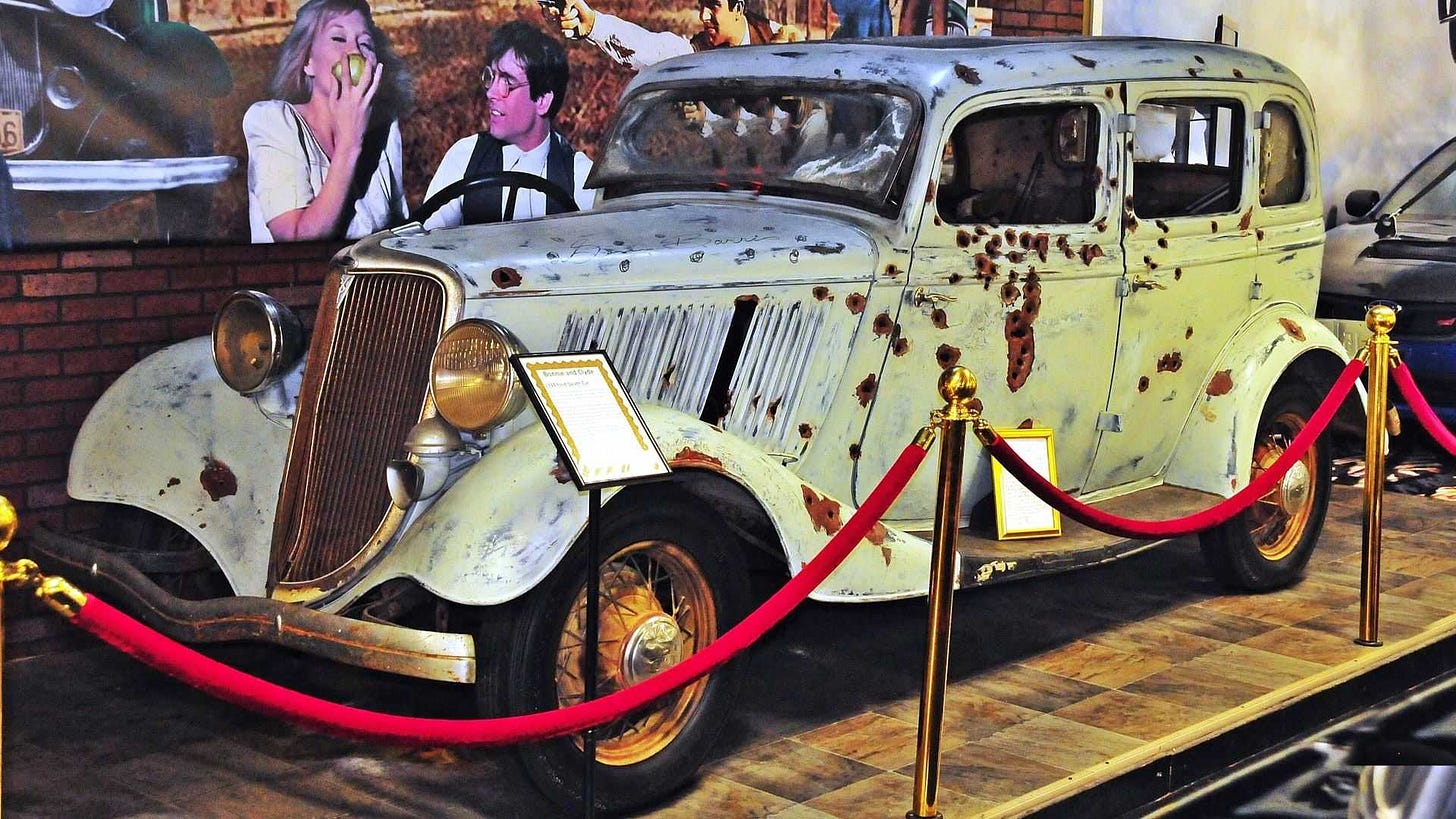

Students at nearby Arcadia High School ran from the schoolhouse as the bullet-riddled death car was towed into town. One of the young girls was my wife’s mammaw, now ninety-three. The vehicle was put on display at the Ford dealership, and the bodies of Bonnie and Clyde laid out on tables at a local cafe. The town swelled into a carnival as people came to see.

Sheriff Henderson Jordan died in a head-on collision thirty miles from the ambush site, at the age of sixty-five. The twenty-seven years after the shooting had not treated him well. A member of his family wrote that Jordan’s hair seemed to turn white overnight after the ambush, which was never mentioned by the family in deference to his feelings. Reports varied on whether Barrow and Parker were given chance to surrender, tainting the police ambush as premeditated slaughter. The reward money offered for Bonnie and Clyde’s death or capture dried up with the controversy, leaving the hunters who spent months tracking them to fight over souvenirs, their arsenal of firearms, and the car itself, which was returned to the woman it had been stolen from only after a court order. It is currently parked in a casino in Primm, Nevada. Google it if you want the gory details. The cluster of gaping bullet holes is testament to the posse’s marksmanship.

When we visited the ambush site, the road had been paved and the ditch filled and graded. It was quiet as a cemetery. Two hunting beagles spied us from the woods beyond the gruesome site’s desolate marker, then ran as we approached. Someone had left the dogs water bowls and a blue plastic drum with blankets for shelter. I wonder if the two lost pups’ names were Bonnie and Clyde.

Wow, amazing background on Bonnie & Clyde, and that’s incredible that your wife’s mammaw actually saw the car. I was obsessed with the movie in my late teens -- I kept making my friend Johnny dress up like Bonnie & Clyde for Halloween which made no sense because I look nothing like Bonnie & no one ever had any idea who we were -- but I think I liked the populist draw of the Robin Hood-ish couple. Finally, Johnny pointed out that they were murders & refused to wear the costume again -- I think he also had a girlfriend at the time -- so that was the end of that, but they are so interesting, with their kind of populist hero and/or crazy mass murderer-lovers thing going on. Thanks for all this info & for talking about the Dust Bowl, about which I should learn more.