I’ve been a fan of Studio Ghibli since I saw Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind at a science fiction convention in the early ’90s; back then was only available on a bootleg VHS with subtitles by fans. Later, I saw Princess Mononoke at the Asian Cultural Center in Minneapolis. So, I thought it was wonderful when Spirited Away won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature in 2003. It remains my favorite of their films, about a young girl thrust into a familiar yet disturbing world all too like adulthood, who faces her fears and uses her resourcefulness and loyalty to friends to make the best of her predicament.

Princess Mononoke was the general American public’s introduction to Miyazaki, and it is an action film, with a war between nature and a village of gunmakers; it’s an easy sell. Spirited Away is a disturbing fairy tale about a young girl kidnapped and enslaved by a witch. It’s Alice in Wonderland in a fairy tale world sprung from Hayao Miyazaki’s imagination, melding all sorts of folklore.

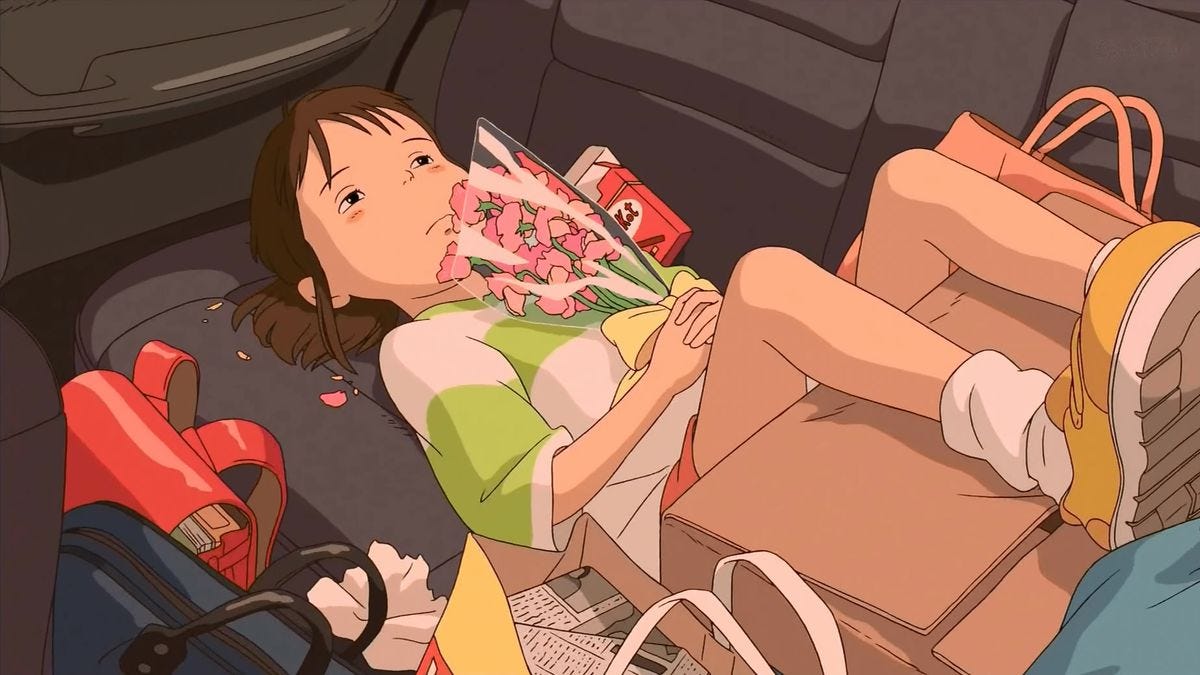

Chihiro is a young girl moving to a new town with her parents. She is angry that they are leaving home, and she mopes petulantly in the back of the car. Her father takes a deep forest road, and they come upon an abandoned shrine. As they explore, her parents find a room laden with delicious food, and eat ravenously. Chihiro senses that something is off, and does not eat; she comes upon a boy named Haku, who warns her to leave with her parents, but it is too late. Her parents have turned into pigs, and there is no return. They have entered the land of spirits, and cannot escape.

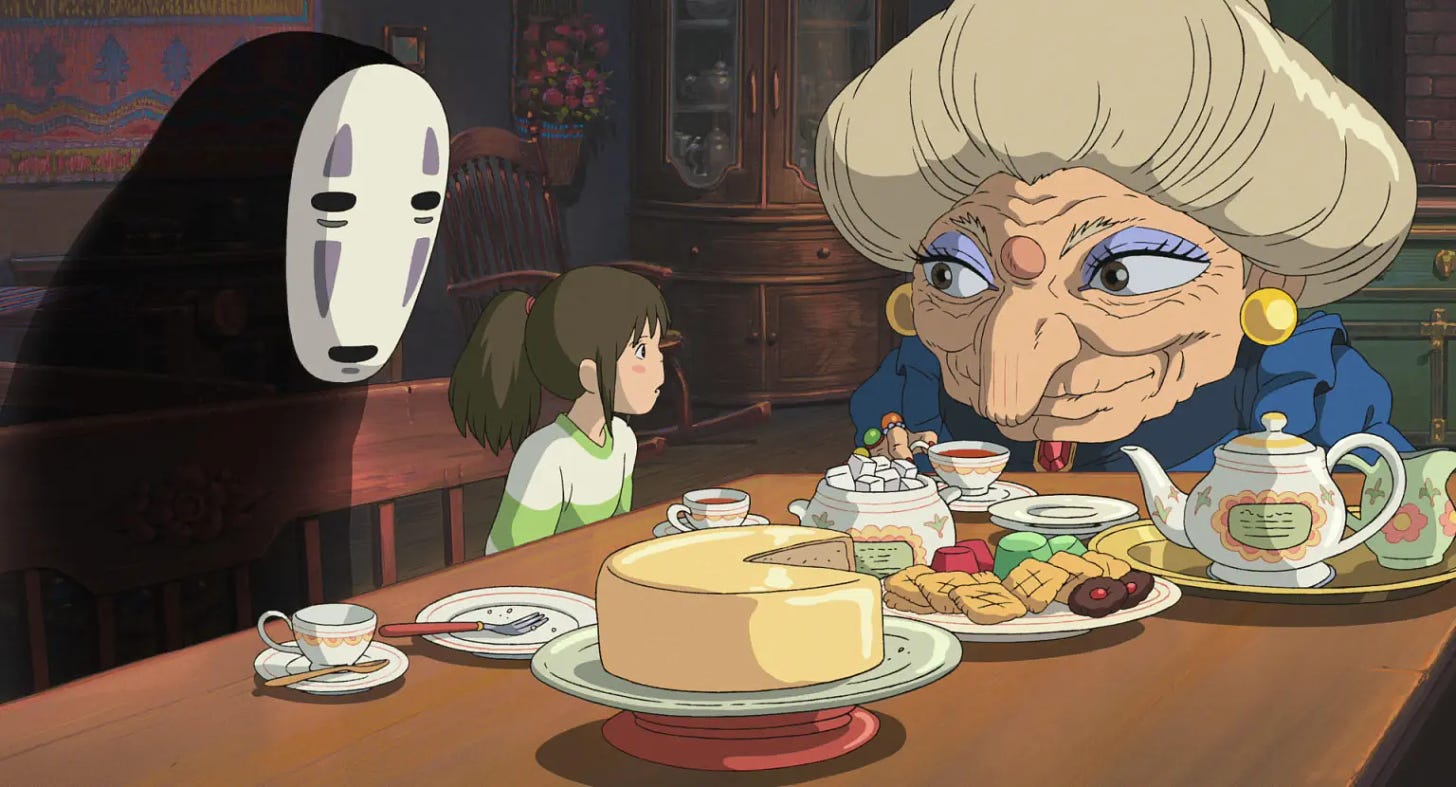

Because we’re not sure that we’re in a fairy tale yet, the transformation is disturbing. Chihiro follows Haku, who wants to protect her, but soon she is in the thrall of the witch Yubaba, a wizened old woman of bizarre proportions. Her parents are kept in Yubaba’s pigsty, and Chihiro must find a way to free them and escape; her only choice is to work for the witch at her onsen, an inn with a hot spring, where the gods come to get clean. From here on, we follow the naive yet plucky Chihiro as she works off her debt in the spirit world, making friends and learning how things work here.

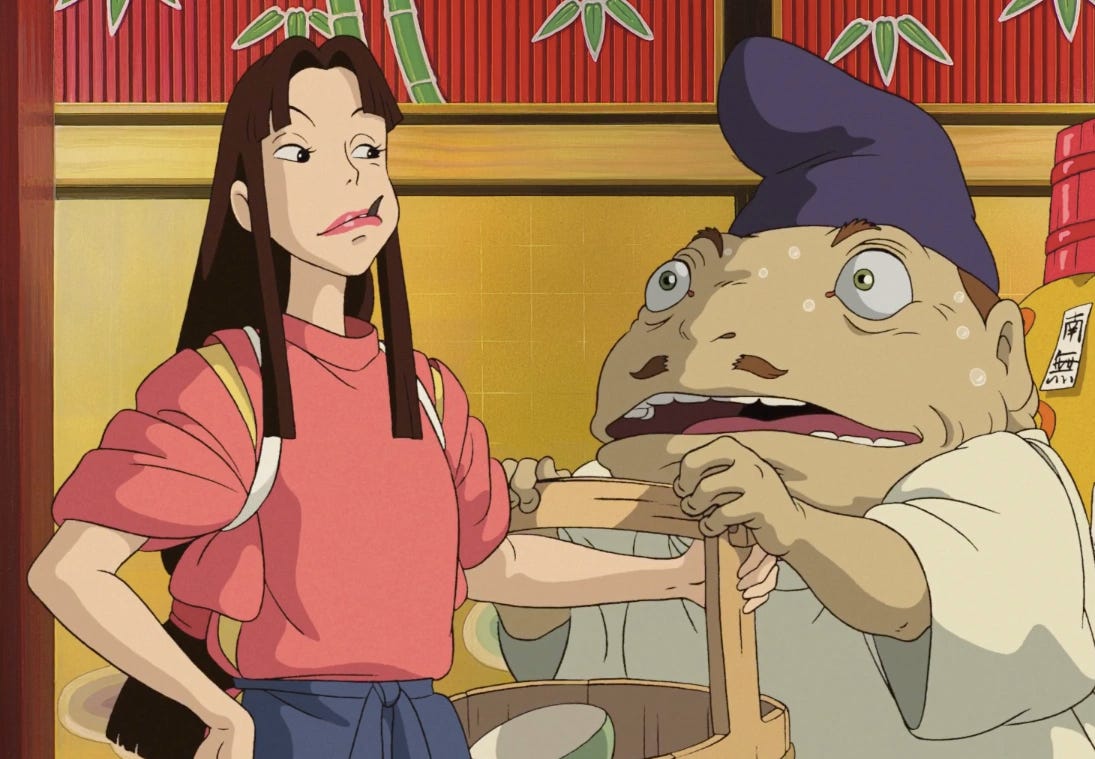

The world is full of mystery and wonder, but rooted in mundane work life. Another worker named Lin—one of the few humans we meet—takes Chihiro under her wing and teaches her the ropes. They toil together scrubbing the bathtubs, which are visited by frog men, dragons and “stink gods.” Some are the spirits of rivers and trees, in other guises; others are pure mystery, such as a cloaked, silent figure in a Noh mask who seems a little too friendly and generous. Chihiro learns that Haku is also bound to Yubaba, and hopes to free him as well.

The story is slowly paced, but there is always something fantastic going on. The characters are full and believable, whether they are witches or drudges. And as always, the beautiful animation of Studio Ghibli fills every corner. Dragons have dogfights in the sky against swarms of paper birds cutting them to ribbons, a spidery man with a dozen gangly limbs operates a coal furnace fed by a tiny army of soot sprites, and we follow parades of spirits and fantastic creatures as they walk across the bridge to town.

This world has the same grip that the creations of Jim Henson and Terry Gilliam have, and it’s not all fun and games. Yubaba takes Chihiro’s name as collateral, and renames her “Sen,” as if capturing her soul. A ravenous spirit begins luring the bath house workers with gold nuggets and swallowing them whole. Yubaba’s minions include a trio of bouncing, grunting, bearded disembodied heads, and a beastly enormous baby that she dotes over. We get a real sense of danger for little Sen, no matter how resourceful she is.

Spirited Away is more than a coming of age folk tale about a child forced to grow up in a strange world. In part, the bath house is a warning about embracing the mythic past. In 2001 when the film was made, Japan was undergoing an economic crisis, and many people were struck with a yearning for the “the good old days.” The story shows the bad side of the past, with Sen’s forced servitude. The familiar Miyazaki nods to how humans mistreat nature are subtle, but there; a polluted river spirit flies away in joy, once it is freed of the garbage that weighs it down. The punishment for the gluttonous parents is a bit less subtle; we have grown ravenous and need to check our appetites, or be slaughtered. As poignant now as ever.

Lessons aside, Spirited Away succeeds as a great story; at just over two hours, it never drags or feels indulgent. It envelops you, as fantasy should. There are mistakes and redemption; people of compassion and greed; selfish vampires, gluttons, and the rewards of earnest hard work, pride in doing the right thing when it’s not easy, and forgiveness for trespasses. We dive deep into a strange yet familiar world, and meet fantastic and interesting characters. Someone eats a dried lizard, and they make it look so tasty you wish you could have a nibble.

Spirited Away is the perfect marriage of the more energetic Princess Mononoke and the children’s fairy tale My Neighbor Totoro, a story that can be enjoyed by everybody. Ghibli has made films of great realism, such as Grave of the Fireflies and Only Yesterday, and this stands with them. It also stands one of the great films, whether animated or not. You can watch it subtitled, or with the excellent English dub that was released by Disney in 2003.

Part of what I love about it is that of the fantastical Ghibli films, it feels the most rooted in the day to day. Sen has to work! And the plot is simple for a film of 125 minutes; Sen makes friends and gets in trouble, but it’s not full of strange twists just to fill the time. When she’s working with Lin scrubbing the tubs, she’s sent to get something from the foreman… and after forty-minute minutes of accepting talking frogs and masked spirits, Sen asks… “what’s a foreman?”

The Japanese spirit of “service” is spoofed a bit when the “Stink God” arrives for a bath. It can’t be turned away, and only Sen is too new to know any better, and takes the onerous task of filling its tub. Her perseverance gets her in good with her boss Yubaba, and makes the spirit worlders accept their new “smelly human” comrade. It’s also one of the Ghibli films where they seem almost indulgent with realism, to make the fantasy feel real. Little touches, like when Sen struggles to serve the River God, she drops the tag and has to use another; it must have taken days of work to add those precious seconds, but these moments sell the verisimilitude, and we are along for the ride.

Best of all, some things are simply never explained. No-Face is a favorite character, from his disturbing half-voice, to his iconic mask. He becomes obsessed with Sen, and also becomes her responsibility; we never learn why. Life is sometimes like that. We don’t know why negative people attach themselves to us, and sometimes they become our burden. Sen gives him tough medicine, but is also kind. Good relationships happen the same way; Haku, in his own predicament, sees Chihiro lost in the city and tries to help her. They become loyal friends, and make sacrifices to help one another. We learn that much of life is bittersweet; for Chihiro to save her parents, she must leave her friends and the new world where she has left her mark. In the last scene she is uncharacteristically quiet, and her look back at the tunnel that led to her adventure makes her seem much older than her years. If you haven’t seen the film, it is streaming on Disney+. I’ll leave you with Chihiro, looking no older, but much wiser.

Wonderful! So enjoyed reading your takes from this marvelous film. My brother, who lives in Japan, gave us a VHS of My Neighbor Totoro way back when. I’ve lost count of how many times we watched it. Never gets old. The art in that, and all the films, is magnificent. Our local art house had a Ghibli fest recently and it’s been such a crazy summer I missed every one. (What am I doing wrong in my life???) 😊🥰 Thabks for a great read.

Really enjoyed this. I presume you've read Sam Anderson's piece about Ghibli Park?

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/14/magazine/hayao-miyazaki-ghibli-park.html