Humans like to pretend we’re the last ones on Earth.

There’s something about civilization that makes us want to end it. Those with a vested interest in keeping civilized hierarchy intact like to spread the myth that not only was civilization inevitable in the forward march of progress, but something that your garden-variety human wanted. I say garden-variety because to inflict civilization, those who decided they owned the land needed to use force to make the rest of us tend their gardens. Eventually they started kidnapping people and taking them on ships across the ocean to do it. In Against the Grain, James C. Scott argues that not only did humans domesticate plants into crops and animals into livestock, but also ourselves.

Maybe this is why we separate ourselves from nature. When you see a beaver dam or a hornet’s nest, you may not like it, but you probably don’t think of it as a scar on the landscape, as you would a McMansion peeking through the trees. If you thought you had escaped into “true wilderness,” even a nicely built cabin might elicit a similar reaction. I’ve said before that I think people “see” Bigfoot because even those who live close to the land do not feel truly a part of it anymore; we know, even as we “tread lightly,” and “leave no trace” in the forest, we go home and throw our plastic into the recycle bin, where it will end up in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch or a landfill.

Like all kids born in the ‘70s, I was raised to hate “litterbugs,” and to Give a Hoot, and not Pollute. It wasn’t until recently that I learned that “litter bug” was coined by a Madison Avenue campaign to deflect blame for trash from disposable packaging and container manufacturers onto consumers. This does not mean I throw my trash on the ground. But it certainly makes me think very hard about which “clean up the woods” events that I join.

Last year I helped clean up a few thousand pounds of trash dumped into Collier’s Mill, a northern edge of the Pine Barrens. It was mostly used car tires, which were there because towns no longer pick them up or let you bring them to the dump. You are supposed to pay a disposal fee when you get new tires. But somehow, plenty get left behind. Stuck in a garage because they have some tread, and waste not want not, right? Reduce, reuse, recycle! You might need a tire. But you’re not supposed to mix and match tread wear on many cars. So you’ve got a hundred pounds of trash in your garage and the tire shop won’t take them from you. So you sell the house with them in the garage, and the flipper dumps them in the woods with those fluorescent light fixtures that are illegal to throw in the trash.

And then the state, instead of having Public Works clean up the woods, is more than happy to give a permit to a bunch of Subaru drivers who want to do a good deed. And we do it for free.

I mean, I do it because if we don’t, they’ll sit there and rot. But it’s frustrating.

Then I think about how we only know so much about the past because of trash middens like this one, a shell mound that dates back at least 1500 years and supposedly continues at least nineteen feet below the current ground level:

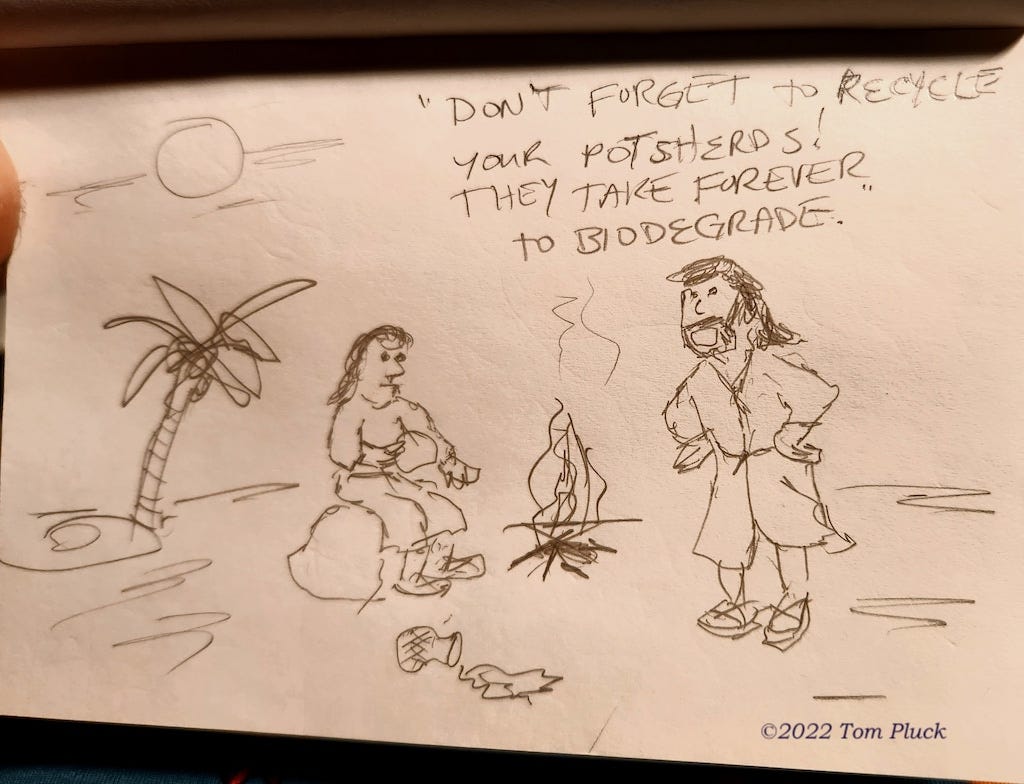

We don’t like to think that our civilization will collapse, but it wouldn’t be the first time. The Bronze Age collapse of 1177 B.C.E. may be why cultures we consider ancient often speak of a “golden age” before them. Here’s hoping we manage to transition to a civilization that treads more lightly upon the Earth before we collapse! But we find historic value in the trash of those before us, even if their civilization didn’t collapse. Mudlarks on the Thames find treasures, as do hunters with metal detectors, and archaeologists of the more recent past. Thinking about that, and our current obsession with “leaving no trace,” inspired me to draw this cartoon:

This is not to say I want to see vending machines on top of Mount Baldy, or candy wrappers spangling the trees when I go for a hike. We should tread lightly, because there are 8 billion of us, and we outweigh all the other animals on Earth. And our livestock weighs even more. I cooked a good steak last night, but mostly I skip the beef these days, because of how heavily our cow obsession treads upon the Earth. I really don’t miss it, and I’m the guy who ate a ten-patty burger less than ten years ago, to celebrate deadlifting 555 pounds on my forty-fifth birthday.

We’ve left so much a trace that they’re calling it The Sixth Extinction. Sometimes it gives me hope to follow people like Matthew Christopher, the photographer, writer, and podcaster behind Abandoned America, and see just how quickly the scars of human civilization are healed over by nature. So when I tromp through places like the Brooksbrae Terracotta Brick Factory in the Pine Barrens—and see how it has been painted over and over by taggers, in a Pompeiian palimpsest of graffiti—I am not so concerned.

I’m more worried about the trash we’re dumping into the ever-more-acidic oceans, the fumes my car is pumping into the air, and the fact that even in South Africa, where solar power seems a no-brainer, they are burning coal and their power is out because the plants are falling apart:

Hannah’s newsletter is one of the best. Another enjoyable read this week, from another newsletter that I Officially Recommend, is Joyce Carol Oates on her father, and how we mythologize our parents. We never really know them. Often when they die, we become archaeologists and trowel through the trash middens of their “civilization” and discover people we never knew, for good or bad.

Chris LaTray shared a gem from Nick Cave on his newsletter, and if the state of the world has you angry, this may help you remember that there is still wonder; that for every dead humpback whale that washes up on the beach, there remains a pod of them, still bravely singing.

I get asked about my rage a lot, how I manage it. Some days I do, some days I don’t. But I try very hard to not live in rage, even as it swirls inside me; to not be cynical, to try and face it all with love. Some days are better than others. I think closing with this from Nick Cave’s Red Hand Files is a perfect way to end. Nick nails it, as he so often does.

When did you become a Hallmark card hippie? Joy, love, peace. Puke! Where's the rage, anger, hatred? Reading these lately is like listening to an old preacher drone on and on at Sunday mass.

ERMINE, GRAND MARAIS, USA

Dear Ermine,

Things changed after my first son died. I changed. For better or for worse, the rage you speak of lost its allure and, yes, perhaps I became a Hallmark card hippie. Hatred stopped being interesting. Those feelings were like old dead skins that I shed. They were their own kind of puke. Sitting around in my own mess, pissed off at the world, disdainful of the people in it, and thinking my contempt for things somehow amounted to something, had some kind of nobility, hating this thing here, and that thing there, and that other thing over there, and making sure that everybody around me knew it, not just knew, but felt it too, contemptuous of beauty, contemptuous of joy, contemptuous of happiness in others, well, this whole attitude just felt, I don’t know, in the end, sort of dumb.

When my son died, I was faced with an actual devastation, and with no real effort of my own that posture of disgust toward the world began to wobble and collapse underneath me. I started to understand the precarious and vulnerable position of the world. I started to fret for it. Worry about it. I felt a sudden, urgent need to, at the very least, extend a hand in some way to assist it – this terrible, beautiful world – instead of merely vilifying it, and sitting in judgement of it.

Perhaps, Ermine, you are right, and I did, for good or ill, turn from a living shit-post into a walking Hallmark card. But, well, here we are, you and me, sending smoke signals to each other across a yawning ideological divide. Hello Ermine, I drone, hello.

Love, Nick

At Ulm Pishkun, the buffalo jump near Great Falls, MT, that is now a state park, Indigenous people gathered there for millennia to cooperatively hunt buffalo, which also benefited every other meat eating relative – bugs, bears, ravens, wolves, eagles, coyotes, et al – in the area. When archaeologists dug into it, they found a bone bed thirteen feet deep extending the entire mile length of the cliff. Which tells a couple tales: one, that's a lot of dead buffalo, which also means a lot of surviving everything else. And another would be the "Indians used every part of the buffalo" trope. Which is true, we just didn't use every single part every single time. That doesn't mean we were wasteful. But we did practice a reciprocal relationship with all of our relatives, which is what modern humans have veered wildly away from.

Thanks so much for the shoutout.

There's one extra potential infuriating step on the good-people-trying-to-do-good-but-somehow-getting-caught-in-some-kind-of-capitalist-trap-where-they-end-up-contributing-to-the-problem loop that you describe. That's when, at the end of it, not only have the volunteer-minded-individuals done a favor for the industry that should be paying to clean up the environmental mess that they left, but also the good-hearted-volunteers have destroyed some kind of local industry or economy into the bargain too. This happens for instance when wealthy Westerners donate all their old clothes to poorer countries, thus obliterating the local textile industries and local knowledge. I do it myself sometimes (though sometimes I go out of my way to contribute to a battered woman's shelter, etc.) even knowing that I'm potentially contributing to the problem. These issues are so complex, and sometimes disheartening. If there are tires out there ... sometimes you just gotta stand in the mud and get them out?