You’ve never heard of the Battle of Chestnut Neck? Me neither.

I saw the monument on Google Maps and decided to visit, as it was on the way to a sporting goods shop in the Pines that has the best selection in the area. The monument, erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1911, is more impressive than the battle itself. Look upon their works, ye mighty, and be flummoxed:

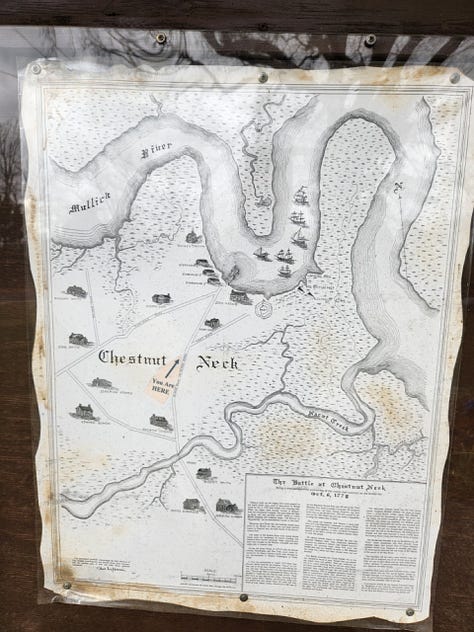

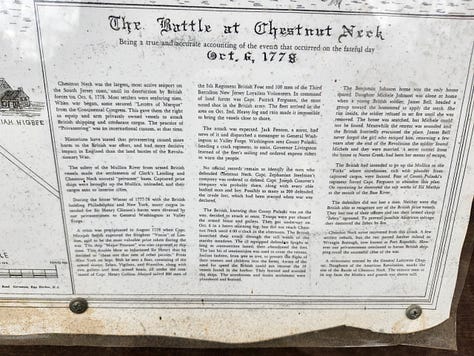

It’s a rather nice monument, depicting a vigilant Minuteman guarding the entrance to the Mullica River, then called Chestnut Neck, in the bustling trade hub of Port Republic, New Jersey. During the Revolution, it was a-bustle with privateers who seized goods from British and Tory loyalist ships, and sold them here. The redcoats were tired of these shenanigans, so they sent warships to attack the rebel city.

Four hundred redcoats faced fifty minutemen, and there was one wounded. The monument honors the militia who fought in all battles in southern New Jersey, which gets short shrift in the history books. Washington crossed the Delaware in Central Jersey, which didn’t exist then—neither did north or south, as the Keith Line divided the state into East and West, a division still felt in town and county boundaries, but not much else. The redcoats were dealt heavy blows at Princeton and Red Bank, and I highly recommend reading the exciting and lovingly detailed Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer for a recounting of those events.

You can read the events at Chestnut Neck as told at the monument, and the memorials, by clicking on the images in the gallery below. I made sure they are detailed enough but not of excessive file size. The privateers who harried British shipping were important to the Revolution, and Southern New Jersey is quite proud of them, rightly so. Much of the cannonballs used by the Continental Army were forged in the ironworks of the Pines, like Batsto, and the outlaw spirit of the Pines remains in folk tales of robber Joe Mulliner. You can read more about them in Smuggler’s Woods by Arthur Pierce, if so inclined.

The Brits were also walloped by General Casimir Pulaski, he of which the infamous Pulaski Skyway is named, a few days after they mucked around at Chestnut Neck. Pulaski was a feared general and cavalry leader who turned the tides of the battle at Brandywine with a cavalry charge, and served until his death in South Carolina, struck by grapeshot while in battle with the French, in 1779. Pulaski’s remains were interred on a plantation and recovered in 1853, and DNA testing confirmed relation with a grandniece. But the forensic anthropologists were puzzled; the bones showed wounds like those Pulaski suffered, but they had female features. It is theorized that Pulaski may have been born female or intersex, and lived as a man. Along with the openly gay General von Steuben—who taught the Continental Army how to drill and act as a unit—General Casimir Pulaski, as he wanted to be known, was integral to the success of the American Revolution.

The Skyway is an iconic bridge from Newark to Jersey City that resembles a black iron dinosaur skeleton stretching across the landscape:

The famous Muffler Man from the credits of The Sopranos lives under it, on the JC side. I made a pilgrimage last winter:

The “outlaw spirit” reminds me of a recent read on the rise of agriculture and civilizations, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, by James C. Scott. I think I’ve mentioned this one before; he argues that not only did we domesticate livestock for farming, but also ourselves. Farming grain was always not done willingly, and grain was chosen by the earliest states because it was easily stored, taken, and taxed. The earliest city-states of Sumer practiced slavery, usually war captives. Because you needed cheap labor to make it a profitable enterprise. (See also the antebellum South, and the continued use of exploited migrant farm labor.)

The other side to this are the people called barbarians by those who rule the State. “Barbarian” originally meant those who lived outside the Greek city-states, and the word mimics their languages, which sounded like someone babbling “bar bar” to the Greeks. More so, it meant people who would not farm or stay in one place so they could be easily taxed by kings. Peoples who refused domestication, and could do so because they lived off the land through a combination of small plot farming, hunting, foraging, and pastoralism, such as raising livestock like sheep and goats, which can be taken up into the mountains and hidden come tax time.

Places like the Pinelands, the mountains of Italy, the bayous of Louisiana, the highlands of Scotland, Basque country, the Ozarks and Appalachians, are still known for people not fond of the government and they have ways of avoiding state control because they can live off the land. It takes outright genocide or totalitarian control or both to defeat people who aren’t dependent on one source of food like cereals; it’s why the buffalo were slaughtered, why “poaching” was invented, and the Sheriff of Nottingham had a cozy job, and one reason why hunting and fishing are still highly regulated. The book is a good read (as long as one realizes the author is rather anti-state) and it offers a lot of food for thought, no pun intended. It gives you a different perspective on viewing history, than the narrative that agriculture—particularly of cereal grains—was an improvement and inevitable progression of the human condition.

Most states had slavery, hierarchies and immense inequality. It’s easy to over-romanticize hunter-gatherer-pastoralist communities, but they often had their own hierarchies, because loaning surplus livestock could make you a big shot, then followed by people indebted to you, loyal, or both (think of all those big bad rich ranchers in Westerns). There were benefits; many of these societies were healthier and less stratified. This isn’t meant to say we need to go back to that, but I wonder if the resurgence in gardening, raising chickens, and foraging during and after the pandemic was to regain a sense of self-sufficiency and control in a time when the social infrastructure’s weaknesses and fragility were bared.

Thank you if you kept with me on this ramble, I hope you enjoyed it. Here’s a photo I took of a bald eagle on my morning hike this week:

I dig this. Of course when I hear "Pulaski" I think of "Big Ed" Pulaski of Forest Service fame and the Great Fire of 1910 out here. The firefighting tool is named after him.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5444775.pdf

https://www.timothyeganbooks.com/the-big-burn

I read a book called Indigo Girl about the importance of growing indigo in the south and the woman who worked with slaves who understood the technology. It was really big deal economically…