I don’t believe much in God, but I love movies about the afterlife. The depiction of heaven and hell, neither of which I ever believed in, comforts me somehow. Whether it’s the splendid afterworld in What Dreams May Come or the documentary of Satanism, Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages, it’s one of my favorite fantasy genres. I include movies like Death Takes a Holiday where Death walks among us; angel films like Wings of Desire; the excellent primetime TV series The Good Place, which put so much thought into what an afterlife would be, and yet also managed to be blisteringly funny and heartwarming. I’ll list a bunch of recommended ones after I dig into one I watched most recently, and liked rather a lot.

That was A Matter of Life and Death, written and directed by the duo of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, who were known as “the Archers” and created such memorable films as The Red Shoes, A Canterbury Tale, The Life and Times of Colonel Blimp, and Black Narcissus. They were masters at using Technicolor film and weaving a good, smart story. There was often a mild fantasy element. Or in this case, a strong one.

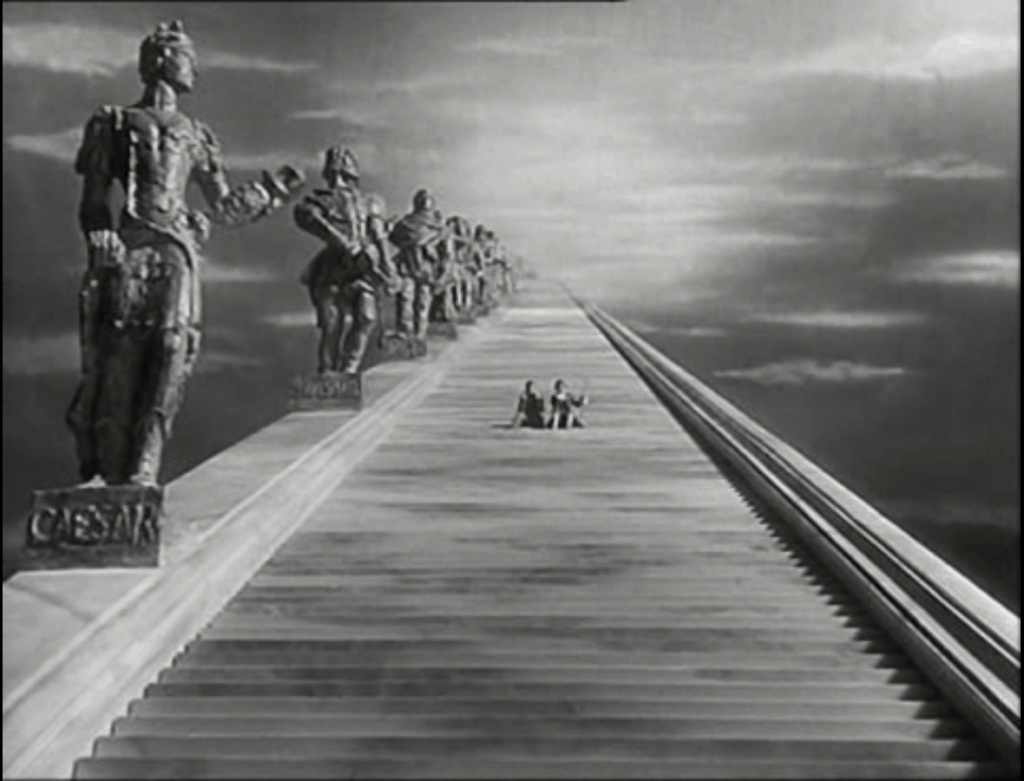

Also known as Stairway to Heaven, for its rather stunning depiction of such, and like a few of their films, is set and was made during the Second World War. It begins in media res, with David Niven as the last survivor on a bomber headed back to England; he’s Peter, the captain, and cradles his dead friend and comrade, Bob, while radioing to dispatch that the rest of the crew have all jumped out with their parachutes. He reaches June—played by Kim Hunter—an American who tries to keep his spirits up as he heads towards home. She’s near the end of her shift, and tells him she’d rather talk to him, as it’s a boring bicycle ride along the beach toward her barracks every night. They like one another.

She tries to get his position so a rescue team can help, but he tells her that all is lost. The bomber is on fire and too far from land, and Niven tells her he’d rather take the leap with no chute—he gave his to a man without—than burn to death. He asks her to telegram his mother and sisters with a dying message, and and that’s the last we hear of him.

Not to summarize the entire film, but it’s rather clever. We next see Bob—with his handlebar mustache like a pair of wings over his smile—in a strange but familiar place. Women work at counters with ledgers, greeting and processing the new arrivals. Bob lingers, watching the entryway. Asking the lead receptionist where his friend Peter might be. He looks eager to spend eternity chumming it up with him. He’s certain he’d be with him, and not routed to some other place…

But Peter does not arrive.

He washes onto a beach, where he strips off his bomber jacket and heavy gear, and walks onto an idyllic scene where a naked young shepherd watches his flock from a hillock on the shore. Peter is certain he’s in Heaven, but no. The shepherd tells him he’s in England. In the very town June mentioned! And down below, a lone woman pedals her bike along the shore, toward a little village…

He’s too excited to see her to question how he survived his jump, and she’s too happy to give it much thought either. They have a bit of heaven together, before Heaven checks its logbooks and send Conductor 71, delightfully foppish Frenchman who lost his head during the Revolution, to fix their mistake and collect Peter. Played by Marcus Goring as only an Englishman could portray him, he is one of the delights of the film, a Puckish psychopomp who can’t fulfill his duty and destroy true love!

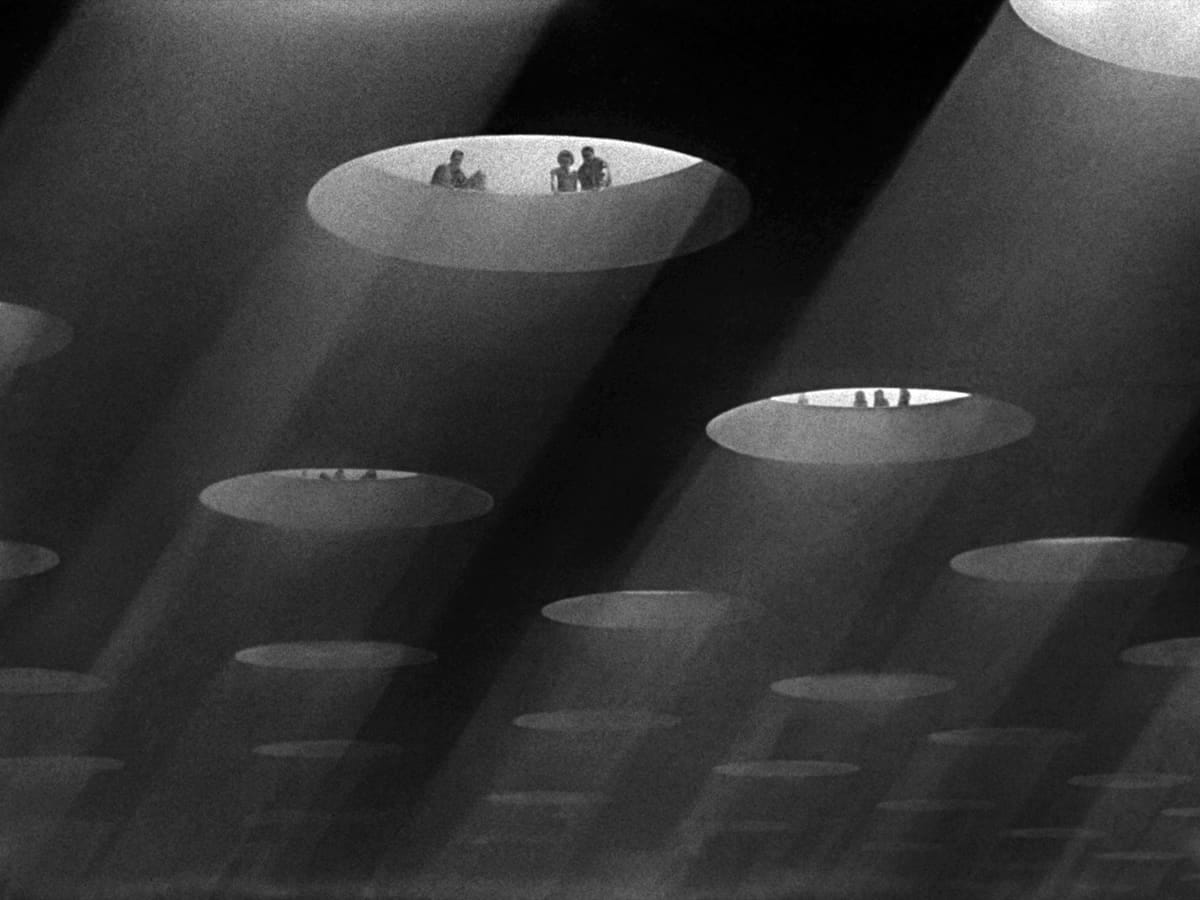

Whenever he freezes time to cajole Peter into willingly returning to Heaven, Peter wakes thinking he’s had some sort of episode. He’s had headaches since landing, and the village doctor, played by Peter Livesey, treats him for a neurological condition and suggests surgery. The brilliance of the script is that you could argue that the heavenly scenes are all in Peter’s mind. He is to be allowed to argue his case at a heavenly tribunal, with the counsel of his choosing, and the trial coincides with his brain surgery. And the prosecution is led by an American who was killed during the Revolution by British soldiers, who hates the idea of a Brit falling in love with a good Yankee girl!

It’s really just delightful, meant to keep the audience laughing and nudging each other over their foibles and those of their fellow Allies, while cementing their common bonds; the best kind of wartime propaganda movie, where the enemy is never seen or even mentioned. It’s blatant when we see the audience for the trial, with buckle-shoed Puritans, Nepalese Gurkhas and Sikhs in the colonial army, American Black soldiers, and Chinese allies all watching to see if Peter can make his case. (Of course they are all segregated, even if it seems by choice… I didn’t say it was perfect).

Another conceit is that heaven is in black and white, and life on earth is in glorious technicolor. A reminder that there may be no pain beyond the veil, but there is no passion, either. You can watch it on Tubi—I bought the Criterion Blu-Ray during their last sale—and I’d love to hear what you think. The Criterion link has a scene with Conductor 71, if you want a taste.

It made me think again about my own concept of the afterlife. What? How does an atheist believe in that at all? Well, let me tell you. We all grieve, and the concept of the afterlife has been a balm for grief since its invention. If our energy is to go someplace after we die, the only energy source I can think of is the electrical fields between the synapses of those who love us and continue to think of us. Who’s to say that our spirit isn’t kept energized by them, and our ancestors, as long as they keep us in the hearts? Rather like the idea that gods are only “alive” as long as others believe in them, aren’t we having an afterlife of a sort in the minds of those who grieve us and miss us, and pass along memories and stories of us?

It’s certainly nice to think about.

Here are some of my favorite movies about the afterlife, if a 1946 film starring David Niven and his em-dash of a mustache isn’t up your alley:

Defending Your Life, by Albert Brooks. So clever and funny!

The Good Place , four seasons of brilliance that you can watch in a week on NetFlix. I am not much of a TV watcher, but this one continually impressed me.

The Lobster (2015) starring Colin Farrell and Rachel Weisz in an absurdist afterlife, where if you don’t find a partner for eternity, you are turned into an animal.

Nine Days (2020) starring Winston Duke and Benedict Wong. A minimalist tale, they interview souls and choose who gets to be born.

Cabin in the Sky (1943) is a musical starring Lena Horne, a delightfully devilish Rex Ingram, and Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, who plays a feckless gambler who dies and is given six months to reform his ways and enter heaven.

Heaven Can Wait (1943) is one of Ernst Lubitsch’s masterpieces of screwball comedy, about a man at the gates of Hell, trying to convince “His Excellency” that he deserves to burn there. The 1978 film of the same title, by Warren Beatty, has an entirely different premise, and is a remake of Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941), in which a boxer taken to heaven before his time gets another shot.

Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey (1991) is the best of the three films, and William Sadler plays Death, straight out of The Seventh Seal, in one of the most sublime portrayals ever filmed. The Bergman film is of course a work of genius, and if you haven’t seen it, do. For another comedy with a few fun afterlife bits, Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life has flashes of brilliance.

Death Takes a Holiday (1934) is a delightful pre-code comedy with Fredric March as Death, who visits Earth as a man, to see why humans don’t like him very much. It was remade as Meet Joe Black (1998) where you can see Brad Pitt get hit by two cars.

There are also ghost movies like The Frighteners (1996) and Ghost (1990) which are like Wings of Desire in that we don’t really see the afterlife much, and thus aren’t as interesting to me, even if they are all enjoyable.

And lastly, What Dreams May Come (1998) is a daring film that kills off an entire family and then tries to make us happy. Some of it is jarring, but its depiction of the afterlife was one of the best uses of computer-generated graphics in film for the longest time. Robin Williams holds it together, and we get both heaven and hell.

I hope you enjoyed this aside, about one of my favorite movie genres.

This Sunday: Nudists in the Pine Barrens!